The Language of Things

Design is both a way to understand the world and a way to increase consumption. Although design was initially understood as a way to solve problems, it creates value and identity and moves between the poles of functionalism and emotion. Art and design have an intertwined relationship that evolves in the marketplace and the museum.

The Language of Things: Understanding the World of Desirable Objects by Deyan Sudjic

Sudjic begins The Language of Things with a common cultural diagnosis: we are drowning in things. He inquires as to why we buy and continue to pursue the acquisition of more and more things. Not only do we have more things, but the things we have are becoming larger. Sudjic asks: what has design become in this time of ever increasing consumption?

Design has become about engineering desire. It is both a way to understand the world and to increase consumption and demand.

The book pursues these two attributes of design: its role in manufacturing of desire and the ways it can be used to understand our lives. It’s similar to the “form versus function” poles typically used to describe design. Sudjic focuses on how design is to create a sense of value and identity.

Seeing design in two ways

Design is the language that a society uses to create objects that reflect its purposes and its values.

For Sudjic, design is a form of cultural expression and a way to persuade us to buy more stuff. In the first, design is how we reflect who and what we are. Design imbues objects with cultural identity and monetary value. In the second, it is manufacturing desire. Design can be an expression of functionalism or emotion, or both.

Creating value and national identity

Objects are the way in which we measure out the passing of our lives. They are what we use to define ourselves, to signal who we are, and who we are not.

Sudjic describes the design of banknotes as an example of instilling a worthless piece of paper with perceived value (other than being backed by national banking systems). Every country’s banknotes portray the deep values of that culture, whether those are historical features, depictions of future events, historical events, or monuments. Sudjic relates an observation that you can tell a lot about a city just by looking at a spoon which was designed there.

Typefaces often have an embedded national identity. Helvetica conjures an idea of Switzerland while the Interstate typeface, made for highways, is uniquely American.

Sudjic points out that each country chooses its own deep identity not only for currency, but also for functional design objects like camouflage. Although all camouflage has the same purpose, each country has its own style of hiding their soldiers. It’s an example of the same problem definition resulting in very different solutions

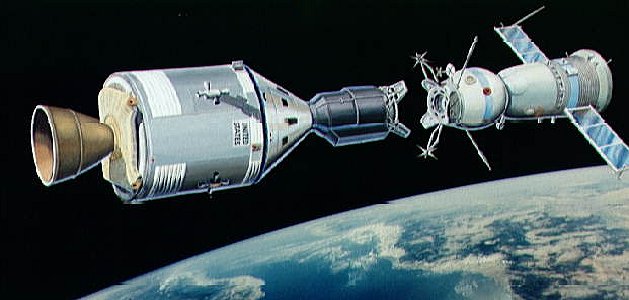

Sudjic points out that although design is often considered to be primarily concerned with solving problems, design is not purely about finding an optimal solution to a problem stated in technical terms. The Apollo and Soyuz capsules were both intended to solve the same problem in the same environment and were created by state scientific organizations, but ended up looking completely different. The Russian capsule is reminiscent of Jules Verne’s fantastic voyages while the American capsule invokes automotive styling of the 1950’s and 60’s.

The technical and commercial considerations do not override the individual identities embodies in the designed objects.

Studjic also discusses the nature of mass-production versus hand crafting. Often, we think of hand crafting as the most valuable due to its rarity; however, Studjic makes the case that the sophistication of Ford’s automotive mass-tooling is far superior to Bentley’s hand crafted approach, leaving an open question of which is better or more valuable.

Value in art and design

Much of the book leads to a discussion about the difference between art and design; specifically, how value is placed on art and design objects in the marketplace and how the two are defined by practitioners and aficionados.

Art has traditionally been valued more highly than design. Art is “useless” and therefore more valuable. Design, with its roots in functional use and domestic concerns, has not only been valued less in the marketplace and auctions, but has traditionally not been viable for display in museums. Stodjic cites several examples of objects which were displayed in museums that broke the mold for traditional artwork: the Bell 47 helicopter and Marc Newson’s Lockheed Lounge.

Sudjic says that “with art, explanations get in the way…with design it is the opposite”. When design is displayed, it is important and relevant to understand who made the object, how it was made, who used it, and how it was used. That kind of context can distract from the enjoyment and experience of art. He gives the example of Picasso’s Guernica. It would not add to the experience of the painting to display pictures of the pilots and aircraft that bombed the city; however, if one were displaying an airplane that had been part of an air raid, including the picture would add meaningful context. There is an ongoing and evolving relationship between what qualifies as art and what qualifies as design. The dividing line is no longer daily use or availability in mass production quantities.

The origins of design

Sudjic uses three iconic designers to trace the history of how design has been defined, practiced, and valued in marketplace. William Morris, who practiced design in the mid to late 1800’s, want to return design to the values of handcraft. He was reacting to the recent proliferation of industrialization and machine based culture. Sudjic sees Morris as the embodiment of the “moral strand” of design. Morris believed that design can make everyday life better. In Morris’ time, there was introduced a split between the craftsman and the consumer whereas before the craftsman delivered directly to the customer. This was also the beginning of designers as critics of industrialization which was ironic because without industry, design would not exist.

Raymond Loewy, on the other hand was “designer as super salesman.” He famously said he would “streamline the sales curve” and wanted to move design out of the domain of function and into the realm of emotion for the purpose of commercial success. Loewy wanted to take design beyond simple utility and use its power to seduce and entice. With Loewy, designers now became a product unto themselves.

Dieter Rams believed in a further transformation of design from fashion to perfection. He wanted to make the perfect radio, the perfect shaver, and the perfect calculator. He chose to blend to the purity of form and perfection of function, but found that technology left him behind in many cases. There are few radios and calculators in use today. As Sudjic puts it, “whole categories of objects have vanished” as the marketplace makes judgements about design value. Sudjic says that Rams “rejected the idea of seduction” and the idea of design which kept changing.

Sudjic also discusses Jonathan Ive, who he identifies as a designer of convergent objects in a time when design is less about permanent values and physical objects than it used to be.

Objects in daily life

Our relationship with our possessions is never straightforward. It is a complex blend of the knowing and the innocent.

Sudjic notes that, as the objects we use become more digital, they cease to age. Mobile phones are now computers which require replacement every year or less. They are damaged by age and do not acquire character through use. Typewriters and watches are no longer available for lifetime use or handing down through generations. Digital technology enables objects to take on multiple purposes (a mobile phone isn’t just a phone) which creates a new type of design that Sudjic doesn’t discuss: user experience. Technological advancement and innovation brings a new set of meanings and opportunities to design.

Sudjic gives an extended example of the telephone and its rituals: once there used to be a single telephone in the home that was located in the hallway and had set of rules for using and answering. Now we carry mobile phones wherever we go and sleep with them at our bedsides, often using them as we first awake. There are rituals associated with every object and those rituals change over time.

Design not only transforms the human interaction with objects, it also transforms entire large scale behaviors. The iPod changed the way we produce, consume, and experience music. Entire ecosystems and business models are altered when new objects come into our lives.

In this video Sudjic presents in the same flow of consciousness way as he writes. In it, he weaves his thoughts together along the main themes of the book.

Although the audio is a bit difficult (there’s a lot of noise and a translator talking in the background), this talk is a great summary of Studjic’s book. He discusses all the main themes from the book and show the key examples as well.

Studjic writes in a fluid style–the threads in the book start separately then intersect and weave together around several themes. The Language of Things explores the way in which design can express identity and value and be a way to understand our world. On the hand, it can be a seductive tool for commerce. But those two modes are not mutually exclusive. Art and design intersect and blur boundaries. Design is much more than just problem solving. It can tell a story and express deep emotions. Studjic discusses how art and design have evolved in the museum and auction space. The theme of value goes throughout the book–from the design of currency to the way that design, although typically “useful” is valued monetarily less than art. Studjic offers many observations on the history of design as it winds through museums, auctions, fashion shows, and confers stardom on its adept practitioners.