Tactical vs. Strategic: Where Product Managers Really Spent Their Time in 2019

When Jim, a mid-career product manager, joined his company last year, he had big goals. He saw himself acting as the voice of the market, interviewing users, and collaborating with the data science team to identify trends. He wanted to create a plan and a roadmap to move his product from No. 3 to No. 1 in the market.

But that wasn’t Jim’s reality.

Instead, he spent significant time in meetings with his development team, acted as the top tier for customer support escalations, and took hot calls from his sales team every week. Worse, Jim felt like he shouldn’t—or couldn’t—say no to these asks. Either no one else was available to do the work, or he didn’t have the executive support he needed.

Unfortunately, Jim’s experience mirrors that of many product managers. As a product management and product marketing instructor, I hear about these types of challenges from hundreds of product professionals every year.

The frustration about where teams spend their time is a fight that has raged since product management became a role. Whether you’re a product manager who relates to Jim or you’re an executive who leads a product team, it is possible to change the way you work. And as a result, you can build a high-functioning product team that’s focused on the right activities.

Where does the time go?

During a typical workday, product professionals spend their time on a broad variety of activities, according to the Pragmatic Institute 2019 Annual Product Management and Product Marketing Survey. And the nearly 2,500 respondents indicated that they aren’t completely satisfied with how they distribute their time.

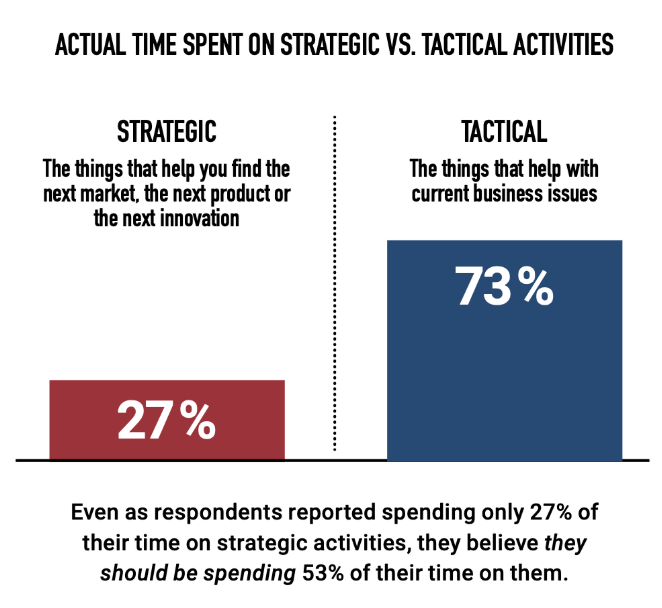

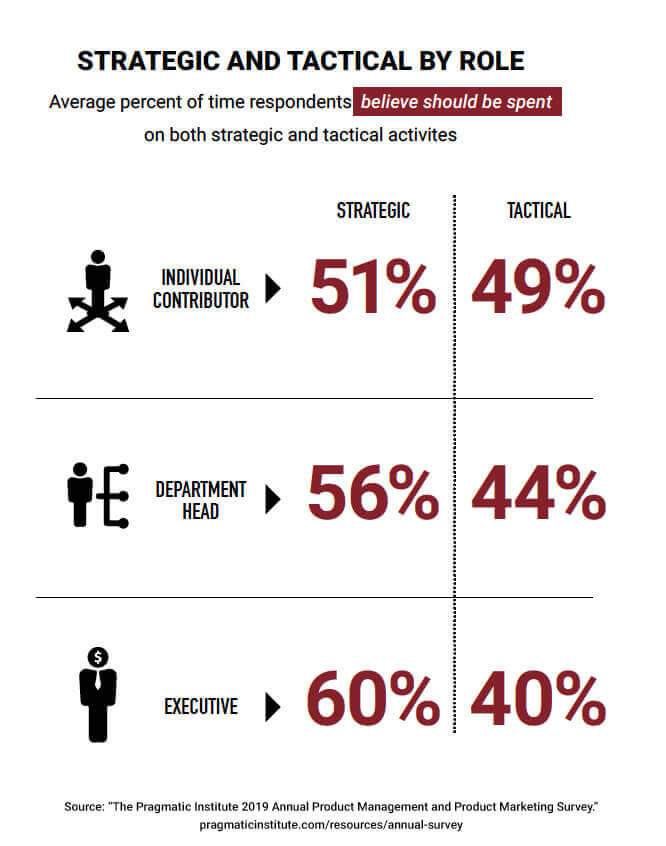

Respondents reported spending just 27% of their time on strategic activities, with the remaining 73% spent on tactics. However, individual contributors said they believe they should be spending 51% of their time on strategic activities. Executives said it should be 60% for them. Clearly, there is a gap between expectations and reality for most product professionals.

At the same time, teams are working long hours. Sixty-five percent of individual contributors said they work more than 40 hours per week, and 42% of executives work more than 50 hours per week. Still, those extra hours aren’t translating to additional time spent on strategy. So, where are they spending their time?

Business activities

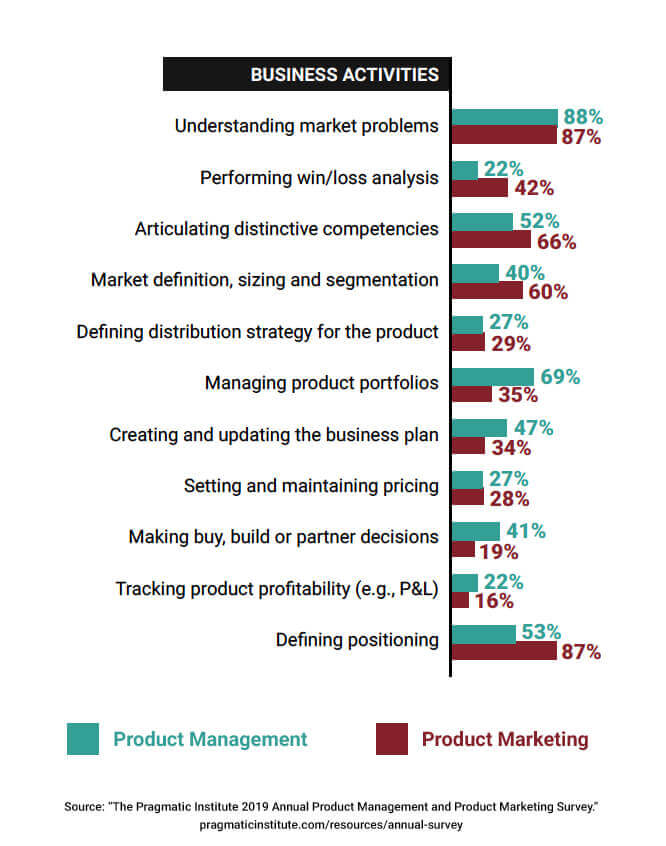

Product managers responding to the survey identified key strategic business activities as part of their roles, including understanding market problems, articulating distinctive competencies, and defining positioning. However, saying and doing are two different things.

When asked how much time they spend engaging customers and evaluators, the results were surprising. More than 74% of product professionals surveyed indicated spending fewer than five hours per month working with customers and evaluators. That’s far less than Pragmatic Institute’s recommended eight hours per week of market-facing contact.

Technical activities

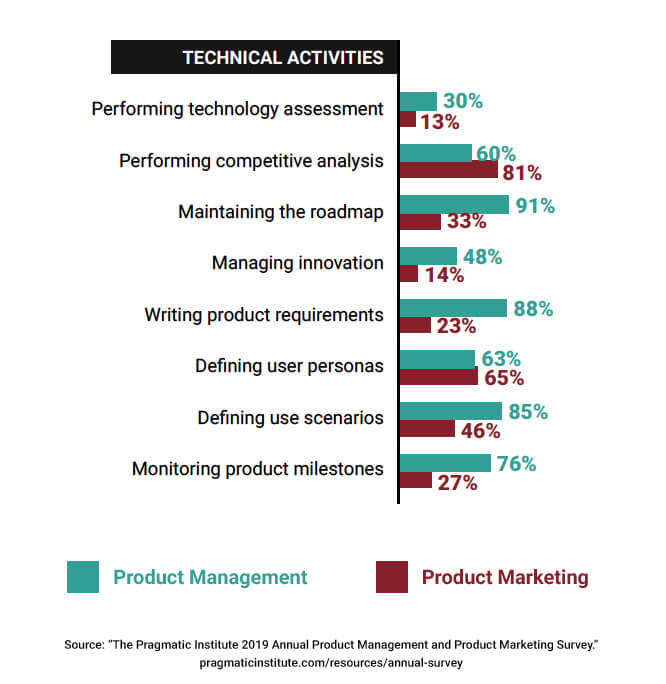

Product professionals also found themselves responsible for a variety of technically-focused activities. These ranged from highly strategic (e.g., evaluating the competition, driving the roadmap) to tactically focused (e.g., monitoring product milestones, creating use scenarios). In this case, you can see the separation of activities between product managers and product marketers. Product managers called out roadmap management (91%) and requirements (88%) as key parts of their role, whereas only 23% of product marketers indicated a focus on requirements.

Go-to-market and sales readiness

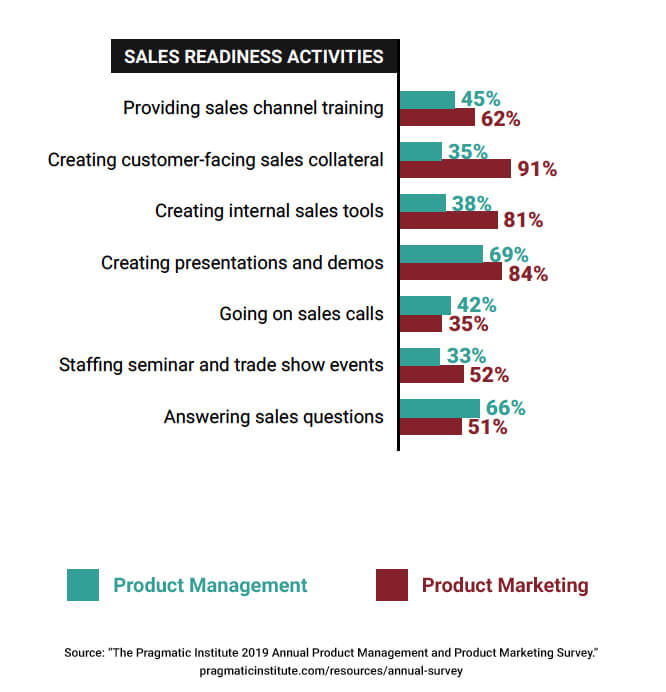

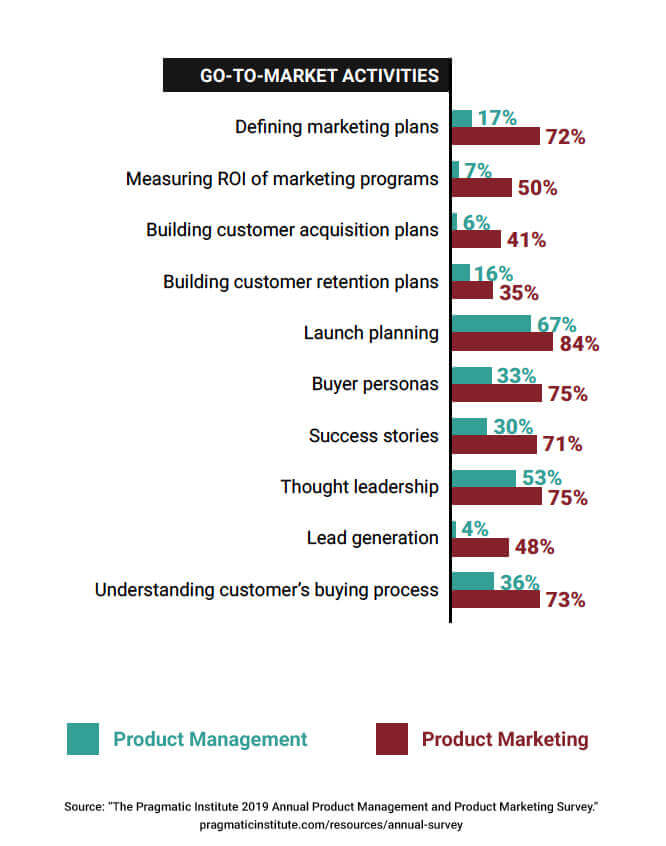

In more tactically-focused go-to-market and sales readiness activities, product marketers strongly identified with their role. More than 70% of respondents said their job included defining marketing plans, buyer personas, and thought leadership, creating sales collateral, and creating demos. Product managers also said they spend time in these areas, especially launch planning, creating demos, and answering sales questions. Three activities that, arguably, take them away from the strategic activities that can help them move their products to that No. 1 spot in the market.

While tactical responsibilities may always be part of the equation, how can product professionals start spending more on strategic activities?

Build your resources

One reason why product professionals don’t spend as much time on strategy is that their organizations don’t provide sufficient resources for tactical work. However, this is both a symptom and a potential cure — if product teams can illustrate the proper resourcing model and organizations pursue the right investments.

Pragmatic Institute has extensively studied the industry-standard ratios of product managers to other roles in organizations. One thing we’ve come to realize is the challenge of strategic versus tactical exists across companies of all sizes. Often, it ties back to the organization’s resourcing models.

For instance, we recently worked with a Fortune 500 executive team whose organizational chart had some glaring gaps. The development team had transitioned to Agile, but the product teams lagged. They had plenty of business analysts and a handful of product managers on hand, but the UX and product marketing teams were almost nil—and it showed in the company’s output. Tactical feature- and roadmap-management tasks consumed all of the team’s time. The important strategic choices that would take the company into the future fell by the wayside.

The company conducted a joint analysis with Pragmatic to look at their resourcing model, organizational structure, and product management processes. The analysis revealed that their team was about 20% under-resourced in product management, dramatically under-resourced in UX and product marketing, and too heavily invested on the business analyst side.

Armed with this data, product leadership was able to work with the rest of the executive team and HR function to transform the organization into a modern product team. Roles and responsibilities now befitted the strategic nature of product management, and it’s a transformation that has stuck through today.

Stop “papering over gaps”

Product managers often come from other departments in the organization, such as marketing, sales, or development. As a result, they’re excellent generalists who potentially feel a constant pull back toward the role from which they came.

This creates a situation in which product professionals inadvertently exacerbate their own problem of being too tactical. They end up covering gaps that exist outside of the product team. An example is when product managers do UX themselves to cover for a lack of UX resourcing.

Product professionals need to recognize when they are papering over a gap by performing activities outside their role. And the issue goes beyond taking time away from strategy. For instance, by participating in an activity they are no longer—or perhaps never were—trained or qualified to do, they’re adding risk to their products. User experience is a perfect example of this. Product managers who find themselves doing this work often produce sub-par user experiences. UX is its own career with its own training for a reason. It requires skills that 99% of product professionals don’t have.

Both product executives and individual contributors should review non-core activities as part of their management check-ins. If non-core activities are present, the executive should gracefully reassign this work to the proper resource and redirect the product professional to more appropriate activities. If no resource exists, the executive’s role is to own a conversation with their peers about how to resolve this gap.

Define and clarify roles

I recently had the opportunity to work with a technology product executive, Vanessa, who was dissatisfied with her team’s performance. She was six months into her role and found that her product management team was too technology-focused. Made up of industry veterans with years of collective experience in the space, the team was laser-focused on product requirements. However, they weren’t business-oriented and struggled to articulate the product positioning and the problems they were trying to solve. They focused so hard on the day-to-day that they didn’t see the bigger picture.

So Vanessa established a common baseline for team communications and built a thorough understanding of the product manager’s role and its scope. Once everyone understood that their roles went beyond the technology and its features, she started dividing the labor. Some team members focused on strategic, market-facing work, while others focused on development. And still others worked on enabling the sales and marketing channels for success.

As product executives develop their teams, providing role clarity is essential. It helps the team retain its focus on the highest-value activities while ensuring that they also cover the full, expansive role of product management.

Say “No”

Many early-career product professionals—and even some seasoned ones–haven’t learned the skill of saying “no.”

“No” doesn’t have to be a dirty word. Many product professionals have Type-A personalities and an innate desire to say “yes” to everything. Unfortunately, because of the aforementioned generalist problem, product professionals face more asks than they can complete.

Instead of using the “hard no,” individual contributors can employ the “yes, but” approach. A hard no—a definitive decline—is difficult if the requestor is an executive, salesperson with a hot deal, or a support person with a customer escalation. By using the “yes, but” model, the product manager can respond with, “Yes, I’m happy to help with your request but, based on the other work on my plate, it will be three days until I can look at this. Would you prefer to wait, or can I help you find another person to assist with this?” This technique takes the sting out of saying no while providing a helpful path forward.

It’s essential that product executives provide appropriate support for the product team to say no. This might mean helping them find alternative resources to take on hot escalations. It may require difficult conversations with other departments if the ask will displace more strategic work. Product teams who feel like their executive always redirects their work to the escalation of the day will not feel confident when the same executive tells them to “get strategic.”

Success is a journey

Product professionals want to be more strategic, but being strategic takes time and energy. Individual contributors and product executives must provide support for one another to make this shift occur. And this change might entail difficult conversations about resourcing and prioritization. However, the value that product teams provide to their businesses when they fulfill their strategic role makes the journey well worth it.