If you’ve ever worked with someone you didn’t trust, you will know why trust is important in the workplace.

Teams that don’t trust each other don’t work well together. Morale, productivity, staff turnover and outputs suffer. Much of the talk around ‘trust’ in business is woolly, misunderstood and lacks clear and actionable frameworks for you to make things better. Drawing on personal experience and a lot of study, Gareth will help you to appreciate how trust issues may be limiting your company’s growth and the role you might be playing in destroying trust.

In this talk delivered at both BoS Conferences in 2019, Gareth shares some concrete and clear steps you can take to build a culture of trust with your peers, your investors, your team and your company.

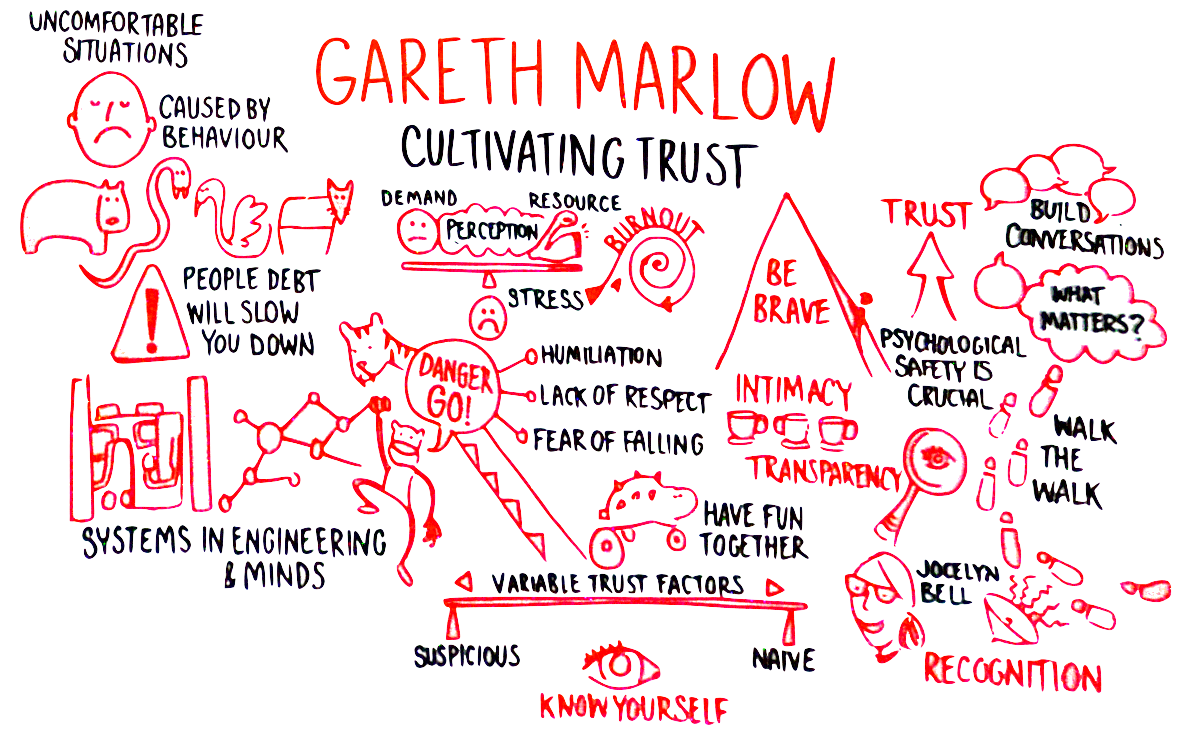

Find Gareth’s talk video, slides, transcript, sketchnote, and more from Gareth below.

Find out more about BoS

Get details about our next conference, subscribe to our newsletter, and watch more of the great BoS Talks you hear so much about.

Video

Slides

Sketchnote

Transcript

Gareth Marlow

Hello. I find it very hard to fit the music to the mood. And there’s nothing worse than to make the wrong choice.

Gareth Marlow

So I want to talk to you today about uncomfortable situations. So, maybe it’s the CTO who nobody in marketing will go and talk to because it always feels like they’ve done 10 rounds in the ring with them afterwards. Maybe it’s that project manager who always seems to leave somebody in tears each week after a one to one. Maybe it’s the head of sales, who says: don’t speak to anybody in development, they’re all idiots. Or maybe it’s the CEO who spends two weeks of each month dreading the upcoming board meeting, and the next two weeks, trying to recover from it. Before I move on, for those of you who are parents and photographers, you’ll recognize the dilemma that I was in at this point here. Do I keep the 50 millimeter prime lens on or am I going to change it for 100 mil. And so we have a number of different animals in our organization, zoo. And we heard this morning, a lot about the hippo highest paid person’s opinion. So you know, the situation, you’re discussing a complicated problem, you got a group of you together, you’re working your way through it. And then the boss walks in and says: This is what we should do. And that’s it. That’s what you’re doing. Right? That’s the hippo as the red balloon. But there are others. Who knows what this is: Cobra. I thought that that job was only going to work in Cambridge, England, the Cobra sits there quietly doesn’t move very much. Waiting for its chance. And then bam, strikes out, takes out its victim with a harsh word cutting observation. Or perhaps it’s the wolf that hunts in packs, tears, it’s late, turns its victim limb from limb. Or maybe the swan swims along serenely young behind them. Until there’s a sign of attack or threat, at which point it rises out of the water, wings outstretched, hissing.

People Debt.

The problem with this stuff is it doesn’t sort itself out. If you leave it, and you neglect it, it gets worse. And I call this stuff People Debt. So people debt is like technical debt. But for people. And if you don’t sort it out, if you don’t find a way of paying it down, if you’re lucky, it merely slows you down. It merely gets in the way. If you’re unlucky, it can kill you. So like with technical debt, people debt is kind of okay, the organization finds a way of working around them, they will find the people who are capable of going in and facing up to that person who’s difficult, right until the point where you need to make a change and make a change quickly. So maybe somebody key moves on from the team, maybe you need to do something more fundamental, like a big reorganization. And at that point, the people debt rises up and really bites you on the arse because then you find out that, you know, I just can’t put these two people over here together with this person. All this stuff gets flushed up to the surface, and you can’t make the change that you need to make quickly. So like I say, if you’re lucky, this merely slows you down. If you’re unlucky, it can be fatal.

Gareth Marlow

A recent CB insights survey of the reasons for startup failure, one in four of the reasons that they identified were people and relationship related. So the founding team falls apart, relationships with investors break down, burnout, these things are all people and relationship issues and they can kill you. And in fact, the number one reason in that survey for startup failure was no market need. And I would argue that no market need really means we failed to identify that we didn’t have market need early enough, and then pivot to actually find market need before the money ran out. And now to what extent is that process inhibited when you’ve got this people get in the way.

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.

Gareth Marlow

So, to tell you a little bit about myself these days. I’m a coach. And I work with leadership teams, and fast growth technology companies. But when I was a kid, this is what I wanted to do. So I grew up in the northwest of England, we’re surrounded by a lot of Chemical and Process Industry. And I kind of saw this stuff when I was a kid. And that is cool. I mean, it’s just me. That’s cool, right? So it’s cool, for lots of reasons, right? It’s big, and it’s metallic, and it’s shiny, and it’s noisy, and lots of steam comes out and you make cool stuff in it. And the other thing that’s cool about it is, it’s really just a great big analog computer. And you’re trying to use it to solve for things like product, oil quality. But it’s complicated. Because you’ve got all of these complex feedback loops going in, you’re trying to recover the heat from the product that you’re made, and you’re trying to recycle it back. So the warming up the feeds, feedstock and all of these sort of nonlinear loops going in this complex dynamic system, and just kind of really, really interesting stuff. So I took myself to university and got myself a degree in chemical engineering. But unfortunately, when I was at university, getting my degree in chemical engineering, the internet kind of happened. And I guess that was a reality for several of us here. So there was this new world of other interesting systems to go and build to go and do interesting stuff that performed in interesting ways. So really, you know, first inception of my career, and the first part of my career was about working with systems. But these days I work with people and work with organizations, and really I’m still just working with systems.

Gareth Marlow

So if we want to understand what is going on with these people and relationship issues, we need to take a kind of systems type of approach. And our brain is a complex system. There are a number of discrete parts, all of which are responsible for different functions like logic, and language and emotion, and regulating the body at a low level. And it’s an important sort of set of subsystems part of the brain called the limbic system. And this is something that the author and academic Steve Peters calls the chimp. So the chimp is responsible for the survival and the continuation of the species. So basically, the four F’s fight flight, food, and… reproduction. And it’s very important to us, it’s a very important job. Because if it wasn’t for this chimp, none of us would be here. If it wasn’t for the chimp, our ancestors would have been killed, would have been eaten, wouldn’t have been motivated to make more of themselves. But it’s not very subtle. It’s not very complicated. It’s just a chimp, right? So we can actually go now live to the chimp of one member of the audience, let’s see if we can work out who it is.

*assorted Motorhead*

You and me, baby ain’t nothing but mammals. So let’s do it like they do on Discovery Channel.

Gareth Marlow

So the chimp, not very subtle, awesome, but not very subtle. And the chimp is very helpful if we’re in a life or death situation. So if a tiger were to walk into the room right now, we wouldn’t be pulling out our laptops and building out a spreadsheet to try and figure out the different options for what we should do. We wouldn’t be sitting around in a circle at the front telling each other how we were feeling and just kind of checking in with each other. We’d just be running hell for leather, for the exit and for safety, because that’s what we need to do. But for most of us in the working environment, we’re not really in life or death situation. If the chimp has still got a job to do, the chimp has still got to protect us and to keep us safe. So instead, the chimps focus is on questions of status and identity. So the chimp is triggered under these circumstances by things like humiliation, lack of respect, being excluded, lack of support, being misunderstood, confrontation, and injustice. And indeed, for about one in four of us, our chimps are actually quite sensitive, sensitized to this stuff going on with other people in our presence. So if other people that we can see are experiencing these things, then our chimps are triggered.

Gareth’s Chimp.

So an interesting story, actually. So four o’clock yesterday afternoon, Mark grabbed me and said: Gareth, I have had a speaker drop out tomorrow afternoon, is there any chance that you could step in and give your talk from Cambridge? Who’s seen Chernobyl? A few of you. So I haven’t watched it. I was watching it on the plane over and just the first episode, and this, you know, obviously, we know the story of this, this breach of the nuclear power plant, there’s all these people in there, they don’t realize how serious it is. And then they come out and they start sort of mid conversation, just start spontaneously vomiting, it was like chatting away. But well, that was my reaction. That was my reaction, when Mark said to me, is there any chance you could do it tomorrow? And not because I’m under any physical threat right now. But what my chip was doing when Mark said that to me was it was being triggered by the fear of number one. So tomorrow afternoon, you’re going to stand up there, you’re going to make an idiot of yourself, you’re going to be completely humiliated, I had a physiological reaction to that thing, very powerful physiological reaction to that thing going on. Fortunately, the only reason I’m not doing it now is because I now have my face on adrenaline instead. So that’s good. So let’s just drill into this chimp reaction a little bit more. I live in Cambridge, England, and near to my house, in the middle of town, there is a large department store. And when we are in town at the weekend, shopping as a family, we will sometimes go into this department store with the kids, because it’s a nice break. There’s a nice cafe in there. Nice view over Cambridge, it’s a really nice place just to go on the weekend. And what you need to know about me is that I’m scared of heights. And this cafe is on the top floor of this department store. And so when we’re walking towards the cafe, what I have to do is I have to negotiate the escalators of doom.

And when I’m on the escalators of doom, all that I’m thinking when I’m on here is: oh my god, there’s going to be cracks in the side of the building there. If this starts disintegrating is the escalator going to make it down to the bottom bit and safety before I fall down there to my certain death? He’s really sort of racing thoughts, stomach’s in my mouth. It’s absolutely horrendous. And like I say, when I’m in them with the kids, it’s even worse. So this is this is our scene. Okay, we’ve got the escalators of Doom there. There’s the window with a nice view over lovely Cambridge, the coffee shops in the corner. And you’ll notice here there’s beds and mattresses because in this department store, that’s where they display the beds and mattresses. So I go in there with my 10 year old and my eight year old and what the 10 year olds and eight year olds like to do when they see beds and mattresses in stores is they run then they jump on the beds and the mattresses, except when they’re doing that all I can think of is that they’re somehow gonna go boing, boing, boing. And we’ve already ascertained this escalater is gone. Right? So there’s nothing going to hold them back from falling to their certain death. And I lose it. We get down off there. I’ve told you how many times have I told you get off the beds. And I’m really just kind of lose it. And they’re looking at me like what is wrong with dad? Dad’s gone absolutely nuts. Now, I’ve watched this building being built a few years ago. I know how buildings work. I’ve got an engineering degree. We don’t get that much seismic activity in East Anglia. The chance of this building falling down when I’m in it, or when I’m there with my kids is zero. So rationally, I know there is absolutely no threat. I know that. But it still doesn’t stop my emotional override just kind of kicking in and I lose it and I lose the ability to communicate and communicate calmly and communicate rationally.

Learn how great SaaS & software companies are run

We produce exceptional conferences & content that will help you build better products & companies.

Join our friendly list for event updates, ideas & inspiration.

Stress

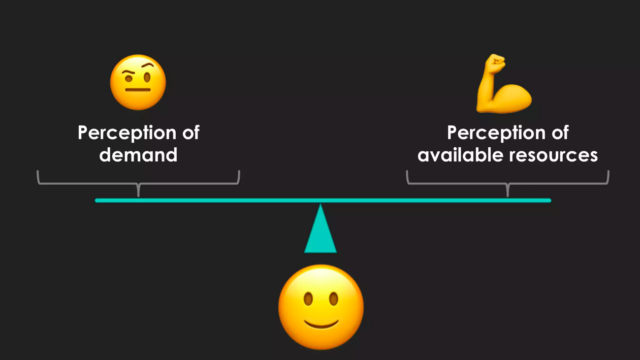

Okay. Just want to talk for a minute about stress. So here’s a useful way of thinking about stress. Imagine in your mind, you’ve got a balance. And on one side of the balance, you’ve got the perception of all of the demands that are being placed on you. So this is all of the stuff that you have to do at work at home. In your life, this is what you have to do. And on the other side of the balance is the perception of the resources that you’ve got at your disposal to try and meet that demand. Okay, so this is your skills, your experience, your money, if you’re in the working environment, maybe the people that you’re managing this is all the stuff that you’ve got to meet this demand. Now, demand is fine. Okay, that side of the which way, I’m looking at that side of the balance, that’s just pressure, good pressure helps us focus, pressure helps us to get stuff done, pressure helps us to keep moving forward. So pressure is fine, until the perception of the demand that’s been placed on you exceeds your perception of the resources that you have at your disposal to meet that demand. And that is stress. Stress is really serious. And it’s really serious. Because it doesn’t just affect the way that we feel, it affects the way that we perform. So when you’re stressed, your emotional regulation goes, your capacity for judging risk goes way down, you tend to catastrophize more. So there’s lots of things about your decision making and your interactions that worsen a lot when you’re stressed. But also physically, you’ve got increased blood pressure, you’ve got an increased risk of having a stroke. There are, you know, lots and lots of bad physical consequences of stress. It’s a very serious thing.

Perception.

Now, if we know that we’re stressed, and we know that there are people who are stressed and are working environments, there are absolutely things that we can do about it, that don’t just involve giving people more resources, or taking away some of their responsibilities. Because the key word here is perception. It’s not the balance between the demands that have been placed on you and the resources, it’s the perception is the critical thing here. So if we want to do this, which is to right size, the perception of the demand, and we want to right size, the perception of the resources that people have at their disposal, essentially, we need to talk to them, because particularly when somebody is feeling very stressed, they’re going to be catastrophizing about the demands that have been placed on them. And they’re going to be underestimating the skills and the strengths and the experiences that they have in order to meet that demand. Because that perception of available resources that you have. That’s just another word for self confidence. And the way that we can really help people to understand that is just by talking to them about it, it’s quite amazing. When you see a stressed person there. Don’t immediately just go away and just try and help them by taking things off them. Or by giving them more people or more resources, that’s not going to be the most effective thing you can do just talk to them. Because this is the game that we’re trying to pray to try to bring this back into balance. The other reason why this is important, is because if you leave stressed unaddressed for too long, it turns into burnout. Now, I don’t know if any of you here have experienced burnout, I suspect that many of you will, but I have. And it was horrible. So over a two, three month period, my perception of the resources that I had at my disposal to meet all the stuff that I had to do was just way out of kilter. And eventually, it just snapped. I couldn’t do anything more. I couldn’t work. I couldn’t think the chimps in my head throwing spanners and bananas, just going absolutely nuts. And the worst thing about it, the blast radius from this burnout affected the people who were closest to me.

Gareth Marlow

That really, really didn’t help. Now, I was lucky because I was in a working environment, which kind of recognized that this might be what was going on. And some colleagues in work essentially, stage and intervention encouraged me to go and get some cognitive behavioral therapy, sort out some of the messed up thinking that there was in my mind, I did some mindfulness, the headspace app really helped a lot of the internal chatter. But ultimately, I went to my GP, my local doctor and had a chat to her. And she put me on a brief course of SSRIs to help me deal with it. Now SSRIs are great, because it’s just a massive dose of Shut the hell up to the chimp. So the chimp sitting there in the corner with his banana, he sorted for me, it wasn’t really a long term solution, because basically I stopped caring, but everything good or bad, you know, family, work, nothing really mattered for that period of time. So that wasn’t something that was going to be a viable long term solution for me. And so I took the steps to pull things together and and then to move forward. But this is not a good place to get yourself into and this is not a good place for your colleagues to get into. And there are things that you can do. There are things that we can do in the working environment to spot it early, and to do something about it.

5 Factors of Team Performance.

Okay. A final piece here in terms of understanding really what’s going on before we can do something about, about some of these people in relationship issues. Google did some work in 2012 I think it was with Project Aristotle. Does anybody know? Anybody heard of Project Aristotle? A few hands, okay. So what they were keen to do is to understand what are the characteristics of high performing teams within Google. So they run a study across around 200 teams, different functions, different geographies, different levels of seniority, and then we’re trying to unpack what was going on on the high performing teams that made them high performing teams. And the first attempt that they had to try and understand this, they failed, they failed to find what those kind of determining factors are, they were looking at things like level of academic accomplishment, they were looking at the amount of time that people had served in the industry or people had served within the organization. And these things didn’t really correlate towards team performance. So they went around the block again, and then tried to find a different set of factors. And then they did identify something that was coherent and consistent and can be used to predict. So they came up with five factors.

1: Psychological Safety

Number one, the most important factor: psychological safety. So for high performing teams at Google, people on those teams felt that they could express themselves without fear of attack, recrimination, humiliation, the fear that this might be somehow career limiting, they can express themselves freely and safely.

2: Dependability

Number two factor: dependability, you will do what you say you’re going to do, when you say you’re going to do it to the standards of quality that we will expect.

3: Structure and Clarity

Number three: structure and clarity, this speaks to a load of stuff, actually, that we’ve heard over the last two days, okay, guys, we understand how this is all going to fit together, we understand how it all breaks down, we understand the processes, we understand how work is going to work.

4: Meaning

Number four: meaning. Our work is personally meaningful for us, the work that we do goes beyond the transactional activities we do on a day by day basis, because we believe and we feel that the consequences of that work are important.

5: Impact

And the fifth factor: impact. I see how I fit in to all of this, I see the role that I play in bringing this meaningful outcome about. And I’m recognized for that.

Gareth Marlow

And what’s interesting for me about all of this is that I would argue that only the middle strike strikes, structure and clarity is really a function of IQ. And the rest of these things have a significant element of emotional intelligence associated with them. And that doesn’t mean that EQ is more important than IQ. Far from it, the problems that we have, are extremely difficult and require our smartest and our best to work on them and solve them. But I think what it does mean is that when there’s some of this kind of interpersonal relationship, chimp brain stuff in the way, it doesn’t matter how smart or how experienced the people on our teams are, you’ll still be massively missing out on the potential of those people, when they’re encumbered by this stuff that’s in the way.

Trust is the Silver Bullet.

Okay, so complex problems generally have complex solutions. But I would argue in this case, there is a silver bullet, there is one very simple straightforward thing to do that we concentrate on. And if we concentrate on it consistently and effectively it makes a massive difference through all of this. And that’s trust. So when we build trust, the chimp is calm. When we build trust, we build a sense of predictability in terms of what experiences we’re going to get. So we’re not sitting there constantly, second guessing: is that person over there, going to screw me over? We’re not there sitting thinking: when I need it, is that person over here going to be ready? Are they going to have done their stuff? Because the trust is in place. Our brains and our chimps aren’t really active within the workplace, so we can concentrate on the difficult intellectual problems that we’re faced with and maybe some of the more difficult chimp problems externally from from the organization.

Gareth Marlow

So what can we do? Well, there’s whole conferences around trust and building trust, and I’ve got under half an hour. So I’m just going to tell you a couple of things that I tried that I was involved with, with one cautionary tale that I have in there. But really what I’m trying to do in this phase is really just to give you something to think about something to go off and explore. Something else that I should say, which is Claire Lew, who I don’t know if she’s here, she’s running a workshop tomorrow afternoon, and there’s huge amount of materials on her company’s website around there. So if you want to go nuts and do a load of reading, I’d really encourage you to go to class session and go to her website. But yeah, I just want to share a few personal things.

Building Psychological Safety and Establishing Purpose.

So the first thing is, I think this psychological safety stuff is part of a wider picture, I think what we’re trying to do within our organizations to build a psychologically positive environment. And that involves psychological safety. But it also involves things like hope, and belief. The things that we are wishing for that when wishing for that we’re trying to bring about. This is the stuff at the top of that Google stack. So we’re talking about the impact that we’re trying to have within the organization, we’re talking about the change that we’re trying to have as a consequence. And so the first thing that I’d like really encourage you to do at an organization level, is really to think about the purpose of your organization, really think about what is your vision for the impact that you’re trying to have, and start using that language and start telling those stories if you don’t do that already. And in my experience, working with lots of technology companies, we kind of, we kind of feel awkward talking about some of this stuff, it feels a little bit grandiose and little bit highfalutin. And what I’m not saying is that everything has to be in the language of: we’re going to change the world and moonshots and all of this stuff. But what I’m talking about is we’re talking about more things than just: what we’re doing on a day to day basis. We’re talking about: what is the change in the world that we’re trying to bring about within this world, just introducing some of that language into our organizations, if it’s not there already. And the other thing is that when we don’t tell those stories, the people who work for us are very hungry for those stories. Anyway, so we’re not telling those stories, they’re going to be telling those stories anyway. So if you want them to be the right stories, you’ve got to get involved and tell them.

Learn how great SaaS & software companies are run

We produce exceptional conferences & content that will help you build better products & companies.

Join our friendly list for event updates, ideas & inspiration.

Establishing Values.

Okay, the next thing to go and tackle at the organization level, I feel is values. And when I say values, I don’t mean the result of some bullshit exercise that your marketing department has gone through with a PR agency, where they’re coming out with a bunch of completely meaningless words that don’t really mean anything. And then they stick them on the slide.

And all that that does is that shows that they don’t understand how Venn diagrams work. I’m loving the strong theme of Venn diagram based gags at this conference, it’s brilliant. Then what I’m talking about is really doing the hard work, to thrash out what matters to you. What matters to you as an organization, what are the behaviors that you want to happen, not just because the law tells us that we have to do them, but because they are the right things to do. Not just figure those things out and communicate them, live them. Because your organization, the people in your organization, are going to follow what you do, not what you say, they’re going to follow what you do. So if you want to have a more collaborative organization, but as a leadership team, you’re not collaborative, what’s going to happen, one of the people going to do who are in your organization watching the way that you behave? Well, they’re not collaborating. You have to walk the walk, you can’t just talk the talk. And there is a sort of a no mega value that cuts through all of this. There’s a value that rises above and, and has a really powerful effect to building trust. And that’s transparency. And by transparency, I don’t just mean okay, the Google Drive is open to everybody. You can go and have a look and see whatever. I’m talking about very honest and open context specific transparency, where there aren’t elephants in the room because you’re actively talking about the issues. So it’s not just we’re opening you can go and see everything. It’s we are sharing with you. What’s going on with us. We are sharing with you what we are afraid of we are sharing with you what we’re actually trying to do. We are Being open, and we are being transparent, it has a massive effect on building trust.

Intimacy.

Okay, so talked about purpose, talked about values. Next thing we want to talk about is intimacy. So this is a photograph of the ground floor or looking down towards the ground floor of Redgate software in Cambridge, which is where I used to work before I started on this career. And we moved into this building in 2008. And when we moved into the building, the ground floor was this kind of completely empty space, nothing apart from a reception desk and some lifts. And then we got a chance, maybe five years ago to to do something more creative with the space that we had. So we’ve decided that we’re going to cut it out and have coffee machines down on the ground floor, and some sofas and places to hang out and just make it a more pleasant environment and use the space better. And Simon, who’s the CEO, at Red Gate said: right, I want to take all of the coffee machines out of all of the other floors. This is a big, tall, three storey building, like really quite tall building, want to take all the coffee machines out from all the floors, and we’re going to put them down on the ground floor. And I thought this idea was nuts. I thought people were going to be wasting their time. I mean, we’ve already ascertained the fear of heights thing, right? Look at those stairs. I thought this was really bad idea. I was dead wrong. It was amazing. So that simple act of forcing everybody down to the same point across the whole business. Whichever part of the business they were working in whichever team that they were in, they had to go downstairs and had to go and get a cup of coffee or their cup of tea. Absolutely brilliant. And just kind of forging those serendipitous links and connections between people are making people see each other as human beings.

The Importance of Playing Together.

And I’m serious about playing together as well. So I guess maybe three years ago, four years ago, we did a speak Salesforce project at Red Gate, and we did a big Salesforce project. Because for the previous 15 years of the company’s life, we have run all of the back end on a set of systems that we’ve developed ourselves. So there’s this huge, organic, monolithic beast where we’d contact management and track downloads and tracked a whole bunch of invoice issued invoices. Yeah, just kind of virtually everything that was a back end process had been automated and built into this, this horrific thing. Redgate is a really good database tools manufacturer, pretty ship CRM system, manufacturer, okay, so while at the time, this is probably quite a smart decision to make in 2001-2002, by the time you’re into the early 2010s, this is not. So we’re going to take the core of this thing out and replace it with something best in class. At that point, this still is Salesforce. But because of the complexity of the systems, this was not going to be an easy job. Okay, because we had to sort of get a hedge trimmer and kind of cut around all of this internal architecture and make sure that everything else was capable of keeping going when we put in the CRM system into the middle. So it was this pretty horrendous waterfall nine month this project with about 20 people internally working on it at different points and handful of really good consultants from a from an external agency. And it all culminated on this day in September, which was deployment day. So on the Friday afternoon, we brought down on the trading systems. And then everybody was gonna pile into the office on the Saturday and do this cutover, test the hell out of it, and then hopefully get everything back up and running to try it again on the Monday morning. So you know, quite scary. Now, if you’ve ever done one of these deployments, you’ll know that there were these periods of intense frenetic activity followed by big long periods. Were you sitting around twiddling your thumbs, because you’re just waiting for data to transfer? Or are you waiting for a script to run? And I knew that people were going to be giving up their Saturday to come in and do this. And, you know, that was a big sacrifice for them. So I thought: Well, okay, I’ll come into the office, but I’ll come into the office via the store. And I’ll go and buy a Wii U, and a copy of Mario Kart and the loader controllers. And then at least we can all sit around and have a bit of game of Mario Kart when we are sitting around waiting for all this stuff to go through. So I did that. And the deployment went well, not related to the Mario Kart, and you know, it was all fine. Now fast forward about three months. A second Wii U has been bought with another copy of Mario Kart. This is now in the office. Around one in three people in the business is having a game of Mario Kart each week. There was this massive Google sheet which is the huge Mario Kart ladder for the organization. Quite automated. Obviously, it’s been slack integrated with custom emojis And they went to town and it was awesome. One of the three people is having a game with Mario Kart each week. And what does that look like when you look for the people who arrive beside of you on the ladder, and then you go and say differently again, Mario Kart, and then you take 10 minutes out, you have a set of three races, and then you record the results in the table, and then you go back and go on with the job. So waste of company time, I would argue not, I would argue not because what it was doing was bringing people together from these completely different bits of the organization, somebody there from finance, somebody there from marketing, somebody there from development, and getting them together for this intense frenetic period of about 10 minutes, where you swearing each other, you’re getting very aggressive, all of this stuff is going on, and then you’re just going on with your day. So a period of time, that’s about the same as a sort of cigarette and coffee break, but applied in this kind of way. And I would argue that’s kind of money and time, very well spent, in terms of bringing and building these intimate connections between people. Because we want to build trust, we’ve got to stop thinking of people as being the idiots in development, or the fools in marketing, and start relating to each other as people. And that was a really good way of doing that. I feel.

Gareth showing off his Mario Kart ‘Skills’

Now, this also gives me the opportunity to show you this video, which has nothing to do with the this talk. It’s just my finest moments on the Mario Kart track. So here’s the context. This is Dry Bowser, this is me at the back and Dry Bowser and my daughter, Sasha Fierce. And just over my shoulder is my wife, racing her pink gold peach. We’re about three quarters from the end of the race. She’s ahead of me, there’s no way I’m going to catch her up. All I’ve got is one banana left. Boom. I think we need to do that again, right.

Learn how great SaaS & software companies are run

We produce exceptional conferences & content that will help you build better products & companies.

Join our friendly list for event updates, ideas & inspiration.

Gareth Marlow

But if you’re going to do this, you’ve got to do this right. So when I was putting this talk together, I went out to my friends and said, Okay, who’s got some interesting, weird stories about trust from the workplace? One friend contacted me and said: Well, okay, I was working in this place. And productivity was low, morale was low. And there wasn’t really a sense of purpose. People didn’t know where they were going or felt a bit flat. So the senior managers thought, well, there’s other companies around here, and they seem to be doing well. So what is it that they’re doing that we’re not? Table tennis. So they went out, and they bought a table tennis table, and they found one under a US Conference Room? And they put the table tennis table in the under US Conference Room? And then they sent out an email?

Don’t Don’t Don’t Don’t do that.

Gareth Marlow

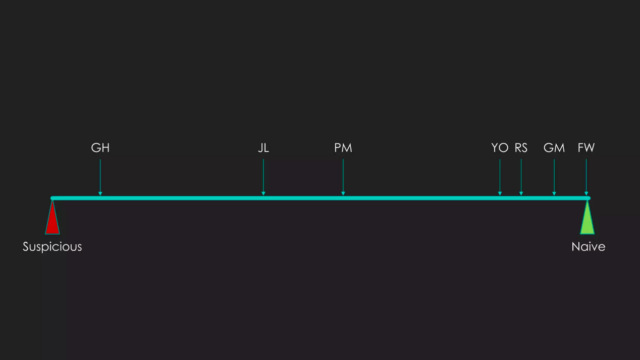

Okay, so practically, what can you do? What can you do with your team? Well, here’s an exercise that I do with teams, if I’m working with them for the first time, and I call this the trust line. So I draw a line on a whiteboard. And one end of the line, I label suspicious. And the other end of the line, I label naive. And I say to people: can you think about the first time that you have to work with somebody new. So this is not the first time you meet them. But the first time you’re actually going to be sitting down and doing some work together? That you’re depending on each of the fourth? What’s your default mindset towards that person? When you’re working with them? For the first time? Is it sort of naive? It’s all going to be fine. You know, they haven’t gotten in, they’re going to screw me over and then I’m going to let me down? Or is it suspicious? I don’t know. So I get people to plot themselves on this line.

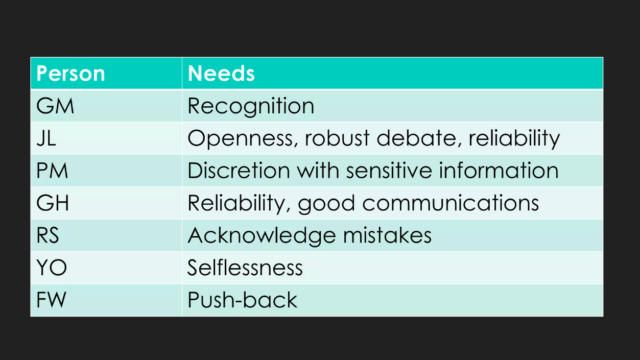

And I also say to them, can you just tell each other what are the factors that shift you in terms of your attitudes, that person that is going to destroy trust was going to build trust? What does that look like? Now for me? I started off over there, right on the Hard right hand side, super naive, everybody’s lovely. Nobody’s gonna hurt each other, just and then, you know, I don’t know. 25 years of adulting, second marriage, seen some stuff anyway, just couldn’t move them a little bit. But I’m still nevertheless kind of pretty much hard over on the right hand side. But if you lie to me, if you throw somebody under a bus in front of me, if you do something to destroy my trust, that may shift very quickly over to that left hand side. And to be honest, when I’m over there, I might over time move back a little bit, but you’re pretty much in the same bin with me once you’re down there on my silk. I properly soak when you’re down there. Pretty childish, but nevertheless, that’s me. That’s how I’m wired. Now, when you repeat this exercise, with the other people on your team, you spot something very interesting. And it’s quite surprising. And that’s the people are kind of distributed all the way across this line. Now I work with a lot with people. And I’m used to sort of being able to try and I don’t know determine what makes them tick. But I can never predict even people I’ve known for a long time, I can never predict where they’re going to put themselves on this line. And I can never really predict what the factors are going to be. That affects whether or not you know how quickly they move, whether or not they’re going to bounce back, and so on and so forth. And I think it’s actually because these factors are largely determined by things that happened in our formative years. So it was not particularly the way that our brains are wired at birth or anything like that. It’s just kind of early stuff, early stuff really affects. And by the time we get to adult years, that stuff is quite a long way buried. Okay, it doesn’t show up on the surface, but it really does affect the way that we think and our sort of default attitudes towards people. And it is absolutely fascinating, because when you go down that list of reasons, you know, what do people need to build trust? What Destroys trust with people, you find that there’s massive variation? So for some people, it’s like, okay, it’s a, you know, it’s important that I get recognition for my contribution. For some people, actually, it’s just about like a one robust debate. Right? If we have robust debate that will build my trust in you.

For some people, it’s about discretion. For some people. It’s about dependability, humility, selflessness. Yeah, push back for some people, like the more you push back against me, the more I trust you, because the more that I believe that you’re actually engaging with me on something real. But the point is this, that when we’re having these interactions with other people, it’s a natural thing to assume that other people think the way that we do. And the reality when you run this exercise, is that that’s not true at all, what’s going on in other people’s heads is very private. And it’s going to be very different from what’s going on in your hand. And the only way that we can really get towards what we’re trying to do, which is sorry, click, which is to move everybody over to the right hand side of that scale, when they have a high degree of trust with each other is to be open, push the user to the surface, and help us to build our understanding of each other.

Gareth Marlow

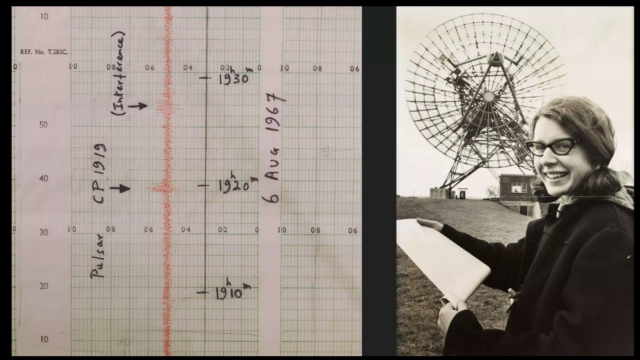

Okay, right. This T shirt that I put back on for today that I was wearing yesterday, getting all sweaty and then Mark said: Can you do the talk tomorrow? I was like, but that’s the t shirt for the torque shirt. So anyway. So don’t get within about a metre and a half of me. Yes. Because it’s quite a sweaty day. Yeah. So anyway, does anybody know where this image comes from? Well, okay, so this image is derived, this image is actually basically the intersection of all of my musical tastes. So it’s basically Acid House plus Joy Division. But the point is that it’s derived from this image. And this is the images on the the album cover of her Joy Division album, it’s just turned 40 years old. Now, the story behind this image is really interesting, and actually ties back to Cambridge where I’m from, because this image is cp 1919. And CP is Cambridge, pulsar 1919. So this is a trace of the first pulsar ever to have been detected. And it was detected here at the Astronomy Department at the University of Cambridge, so the fields from my house. And it was detected in 1967 by this woman, Jocelyn Bell, and she was a PhD student in the Astronomy Department at the time. Now, you need to know the context. They weren’t looking for pulsars. They were looking for scintillation patterns in what they were observing the radio signals. So twinkly, who were looking for twinkling in the radio signals that they were coming in, because for some different reasons, okay. So they have this thing that was recording the radio signals that were coming in from discrete parts of the sky as the as the Earth rotated, and it would just kind of draw this graph on this great big long rolls of graph paper and it was her job every morning to get the rolls of graph paper, to roll them out probably about them get to this stage, get down on her hands and knees and then crawl through inch by inch looking for interesting signals.

That’s what she did. That’s how she did it. So she’s crawling along down here and : what’s this sort of particular part of the sky? This is very, very, very regular signal. What’s that? That kind of shouldn’t be there. Now, the obvious thing, that could be something terrestrial so same time with every night there was a pump that kicks on in a sewage works or I know there’s something that happens on a regular basis. That is cumin originated. So she sort of goes to a PhD student supervisor and says, right, I found this thing and he just dismissed it. Okay, that’s not extraterrestrial, that’s terrestrial. And she had big impostor syndrome around this for quite a long time. So she, you know, she was being brushed off and poo pooed. But she was persistent. And then eventually, she found more of these in different parts of the skies with different characteristics. And eventually, she was able to win over her PhD supervisor, the head of department, and then this stuff gets published and ultimately wins the Nobel Prize in 1974, for being one of the most outstanding contributions to observable astronomy in the 20th century, so wins the Nobel Prize, but not for her. For her PhD supervisor, and for her head of department, but not for her, she failed to get the recognition for her contribution. Now, as a consequence of that, she failed at that point to have been identified as a role model. And I’m still looking at an audience that is mainly men. And I would argue that it is injustices like that lack of recognition, that have gone and contributed to where we are now.

Gareth Marlow

So what’s the relevance of this to my talk? Well, okay, this is a gross injustice. But where we fail to give recognition where recognition is due, where we fail, to really acknowledge the contribution that somebody has made, and even worse, where we give that recognition in the wrong place. It’s hugely, hugely destroying of trust. And one of our challenges leading organizations as we scale is that often we don’t really know what has gone on in the organization, we don’t really know who has done what and why and what their contribution has been. And it’s very easy for us to just kind of think, Okay, well, it’s unknown recognition is important, I better sort of come into the organization and try and spot some stuff and say, Oh, that was really good, that was great. But when you do that, naively, when you don’t give credit where it’s due, it can be massively destroying your trust. So that’s my cautionary tale.

Learn how great SaaS & software companies are run

We produce exceptional conferences & content that will help you build better products & companies.

Join our friendly list for event updates, ideas & inspiration.

Gareth Marlow

So I just really want to wrap up by talking about you. Huge amounts of your ability to understand what makes you tick, what your chimp reactions are going to be, is reliant on your self awareness. Also, understanding what your blind spots are, where your behaviors have negative impact on other people, and you know, you’re maybe well meaning in what you’re trying to do, but it’s having a negative impact, huge amounts of of this trust in this relationship fabric in the organization, and we’re going to make progress with it independent of us knowing ourselves really well. So what are your strengths? What are your blind spots? And what can you improve the challenges that’s very hard for you to to to determine on your own by definition, you can’t see your blind spots. So get help. Ask other people, ask your colleagues, ask the people who work with you ask the people who work for you, as the other people that you have a close relationship with? What are my strengths? What am I blind spots? And what can I improve? Because the more you’re able to build up that picture really of where you are, the more you might have at least a fighting chance of making some of the changes that you need in order to be able to build trust. Now, this stuff that I have sent is not easy. It’s hard. But I would I hope that in the in the course of this talk, I’ve been able to make the case to say that building trust is worthwhile. So this is my parting thought for you. Please have confidence, be brave, and build trust. Thank you.

Question from Audience

Thank you, Gareth. Brilliant, and yeah, you do kind of sweat. Right. Couple of quick questions.

Question from Audience

Thanks for the great talk here. In sort of the Maslow head before, you talked about psychological safety, dependency and a couple other things, some of them seem to be about contributions from leadership. Some of them seem to be about team dynamics. I want to see if you could just expand a bit on the issue of dependability. Okay, which is the one that seems like most emanates from the team members themselves, and maybe that’s an incorrect and could you meditate on that?

Gareth Marlow

Yeah, no, it’s a it’s a great question. I think the biggest challenge I think, with dependability, is not are you actually going to get the thing done. It’s are you gonna let somebody down. Okay, so it’s not actually that I’m gonna do what I say that I’m gonna do. It’s that when you get to the point when you are depending on me, I’m just not leaving you hanging there. So this is something that we can really help team members to think about and help them to develop, because it’s not just about, okay, well, I missed it. I didn’t quite get there. It was late, it was harder, it’s more difficult to help people to understand that this is the impact of being late. And the consequences of you having to do that potentially humiliating thing, which is saying, like I screwed up, or it’s going to be late, or I’m gonna let you down are far, far greater when, when you don’t communicate that beforehand, when you don’t signal that beforehand. So just helping team members to understand like, really what the big impact of them not doing that is. And just kind of, well, again, it’s back to the psychological safety, it’s kind of safer, you’re creating the safety for people to be you know, humbled to be able to take on that is going to be a problem.

Question from Audience

Gareth, great conversation right here. So what that really left me with is there’s an opportunity to create a safety net for people. Right, right. How do you do that en masse in the organization, whether you have 25, or 250? Or more? How do you kind of build that into the fiber of the organization?

Gareth Marlow

I think, you know, it’s about encouraging the behaviors that you want, and about discouraging the behaviors that you don’t want. It is about walking the walk from the top, but you as the organization scales, you know, you can’t hold us all together from the top. So it’s important that, you know, as CEOs, I think you have a particular responsibility to understand just how many eyes are on you. And so that does place an obligation on you to sort of walk the Highline and do those kinds of things. But it’s also to make sure that you’r sort of building this into the systemic fabric of the organization, so that that will be able to scale and be able to replicate. So it’s the behaviors that you reward, the people that you promote, the behaviors that you punish, and those kinds of things, and just being kind of really consistent and being really open about what those things are and why they’re important. So I think that’s the only way that you can make these human relationships scalable as you turn them into the DNA for the organization. And then as more of the organization gets 3d printed out as you scale, then, you know, that’s kind of that’s wired into the instructions.

Question from Audience

Joy Division or Stone Roses?

Gareth Marlow

Stone Roses every time.

Question from Audience

Oh, yeah. Great.

Question from Audience

I just had one question. The young lady whose image you put up there, what was her name?

Gareth Marlow

Jocelyn Bell.

Question from Audience

Jocelyn Bell. That’s it. Thank you.

Gareth Marlow

When I had more notice when it gave this talk in Cambridge, I had a mate sitting in the audience on the laptop, and he was actually tweeting out a bunch of links live. I’ve got a bunch of those links ready to go, which I’ll hop on the laptop. So I’ll put those onto the hashtag. There’s some really nice further articles about what she went on and did subsequently. Absolutely fantastic woman she was awarded. I think it was a 2 million prize recently, 2 million pound prize recently for contribution towards astronomy and physics. And she gave all of that money and put it into a fund to help develop underrepresented groups to be able to come into science. Now that for me is leadership.

Question from Audience

We also had the geekiest crowd ever because I was expecting when you put the picture up, what’s this? And I was expecting all sorts of versions of Joy Division and this that and the other and the first answer that comes out..

Gareth Marlow

in Cambridge, yeah, yeah, yeah. So the first answer in Cambridge is basically, someone just goes: Oh, yeah, that’s cp 1919. Yeah, exactly. Exactly.

Question from Audience

One question. We often reward the loudest person in the room or in the department. What processes or what do you suggest that people do because it’s so easy to be swayed and look at the loudest person and promote them or give them more responsibility? How do you guard against that?

Gareth Marlow

That’s a really great question. I don’t have a good answer for that. I’m gonna guess being mindful of this stuff helps, right. So almost awareness of the problem is one step towards. Being able to do something about it. So just being aware that this is a possibility instantly sort of puts you on to, you know, DEFCON two, and to be more sensitive to it. So maybe just the place to start is just that check. And when you’re looking down it depends on what it is, whether or not there’s a an annual promotion round, or there’s a pay advance round or anything like that when you’re looking at those stages. And you’re looking at the people who are listed for promotion, listed for pay rise, listed for reward, just doing that sanity check there to say: is there a direct correlation here between the people who are outspoken, loud, conspicuous, and the people who are being rewarded, because if that’s the case, then there is certainly a problem. I can remember, I can remember this happening to me. And fortunately, I was working with a really good development manager at the time, I had this set of three project managers that I was working in the division that I was managing at REC eight. And it was Pay Review Time. And I was like, okay, yeah, he’s really good. He’s really good. You know, very conspicuous high profile project managers. And so you know, let’s put them forward for advancement. And my development manager said: What the hell are you doing? Pria is the strongest project manager of all of three of them, just because she’s not high profile, just because you, as a divisional manager are not seeing her conspicuously doing all of the things. It’s like, she’s the most effective project manager that we have in the division, what have you doing, Gareth? So just making sure that you’ve got people around them in the mix, who are able to truly see the who you trust, who are able to have that open, honest dialogue with you and challenge you on those things is extremely helpful. It was a real eye opening moment for me when that happened to me, and very helpful.

Question from Audience

For people that are looking for work, what’s a good way to spot an organization that exhibits bad behaviors like what you’re describing?

Gareth Marlow

Find a bunch of assholes be really motivated by money and nothing else. I mean, I don’t know. That’s a good question. I don’t know. Thank you.

Find out more about BoS

Get details about our next conference, subscribe to our newsletter, and watch more of the great BoS Talks you hear so much about.

Gareth Marlow

Gareth has worked in Cambridge tech companies for 25 years. As COO of Red Gate he launched and scaled products, grew revenue and headcount, and developed (and occasionally fired) scores of people.

He’s worked on acquiring, integrating and divesting companies.At one time or another he managed every part of the business – from HR to sales, product development to marketing, finance to IT. He’s been a BoS attendee for more than a decade and spoke on building trust in your team. He’s now an executive coach and works with tech leaders to help them scale their businesses.

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.