What started off as a memo in 1931 is now widely known as the earliest record of the “product manager” role of today. Every May 13, we celebrate the anniversary of this memo as Product Management Day. What is the history of product management, and how did it start with a memo about “Brand Men” that evolved into today’s Product Manager?

TL;DR

- Product Management started with a memo written in 1931 by Neil H. McElroy, who explained the role of a new position he labeled as “Brand Men.”

- Product management evolved and proved highly successful for decades at Hewlett-Packard.

- Toyota, facing the difficulties of post-World War II, developed still in use product management practices like Kanban and just-in-time and/or lean manufacturing.

- Product management models continued to evolve throughout the 20th century, with models like waterfall, scrum, and eventually Agile.

The Beginnings of Product Management

It’s May 13, 1931, in Cincinnati, Ohio. A junior executive working in the advertising department at Procter and Gamble (P&G) has grown frustrated while working on an advertising campaign for Camay soap. His frustration stems from the fact that Camay soap is nearly in direct competition with another brand/product made by Procter and Gamble: Ivory Soap. Ivory Soap was P&G’s flagship product and as such, other brands, (like Camay), got less time and attention.

This young exec, Neil H. McElroy, starts typing out a memo to justify his recent request to hire more people in the promotions department. The memo broke the “one-page memo” rule created by P&G President, Richard Deupree, as it becomes a 3-page, 800-word document that lays out an idea for a new position that McElroy calls the “Brand Man.”

While the “Brand Man” was going to work in the promotions department, McElroy’s idea was not for some Don Draper type who only worked in advertising. No, McElroy wanted the “brand man” to take complete responsibility for a brand, down to experimenting with and recommending product wrapper revisions. What McElroy was proposing was a radical shift in management where instead of a top-down approach, more decision-making gets moved to be as close to the customer as possible.

McElroy wanted Procter and Gamble to better differentiate between their brands, and, as such, proposed that the “brand men” understand the problems of those they sell to. Specifically, he wanted them to “study the territory personally at first hand – both dealers and consumers – in order to find out the trouble.” He even goes on to say that “after discovering our weakness, develop a plan that can be applied to this local sore spot,” and “make whatever field studies are necessary to determine whether the plan has produced the expected results.”

McElroy was allowed to hire two brand men, and the rest is history. He, with a single memo, essentially created Brand Management and the foundations for what would become Product Management. Many of the duties he listed for the “Brand Men” are responsibilities that today would go by names like “discovery” or “voice of the customer.”

McElroy’s brand men were successful and his idea for brand men and brand management helped transform P&G into an even more successful, brand-centric organization. McElroy would one day become president of Procter and Gamble and, later, Secretary of Defense, (under President Eisenhower).

Hewlett-Packard: Product Management Evolves

Among the many roles that Neil McElroy held in his career, one that may have proved most influential was that of an advisor at Stanford University. In his time there, he became a mentor to Bill Hewlett and David Packard, who further developed McElroy’s “brand man” ideas into principles that would become an integral part of their company, Hewlett-Packard (HP).

Hewlett-Packard was founded in 1939 and at some point in the 40’s the role of “product manager” was officially created. While the “brand men” at P&G worked more closely with marketing and sales, the “product managers” at HP worked more closely with engineering. Much like the Brand Men, the product managers were to understand the problems of their customers and act as their voice within HP.

Hewlett and Packard’s success was unparalleled, including a 50-year record of 20% year-on-year growth. The two built their company on a foundation of principles known as the “HP way.” While most of these principles are known for building a company culture, many of the business objectives set forth in the “HP Way” established a customer-centric mindset. In a meeting with HP managers, David Packard once explained that it’s not about what you sell, but more so, about the problems you solve:

Toyota: From Problems to Solutions

Both the “Brand Man” of P&G and the Product Manager of HP had been given the responsibility of knowing their customer’s problems, and eventually, they would have to build products to solve those problems. Building products is no small task, however, and oftentimes, product managers must solve problems in their own organizations to get products built. It often requires innovation. Such was the case for Toyota Motor.

In post-World War II Japan things looked bleak for Toyota. Frankly, Toyota was on the brink of going out of business. To survive, the company would have to make changes; they needed to do more with less. By the 1950’s Eiji Toyoda, (the nephew of Toyota’s founder and one-day chief executive and chairman of Toyota Motor), was looking for ways to innovate their manufacturing process. Toyoda’s answer came in the form of Taiichi Ohno, a Toyota engineer who was rising in the ranks.

On a trip to the United States, Ohno learned a valuable lesson at the supermarket. He saw that supermarkets only restock once they are nearly out of inventory. They likely have some stock in the back room, but only after that stock is brought to the shelf do they order more. He saw this as a potential model for cutting down on overproduction in the automotive industry.

Ohno wanted to implement a similar system and came up with what would be called “just-in-time manufacturing.” Instead of continuously producing large amounts of parts all the time, (as was the practice in the auto industry at that time), Ohno wanted different Toyota factories to produce only what was needed, when it was needed, and in the amount needed. To help with this, Ohno also developed the “Kanban” system to help aid in the restocking process.

The term “Kanban” comes from the Japanese words “kan,” meaning visual, and “ban,” meaning card or board. If you’ve seen modern Kanban visual work management software, you’re likely familiar with the process of moving a (digital) sticky note from one column to another whenever a process is completed. Ohno created the original (and not digital) version of this process where one department had to wait to make more parts until they got a Kanban card back from another department, with that card indicating the exact number of parts needed in the next batch. This helped maintain the “just in time” process and massively reduced waste.

Ohno and Toyoda’s collaboration brought Toyota Motors back from the brink of disaster. The changes they implemented became known as the “Toyota Production System” and turned Toyota into an automotive powerhouse. “Just-in-time manufacturing” would eventually be renamed to “lean manufacturing” and would be adopted by numerous American companies, including Hewlett-Packard.

Don’t Go Chasing Waterfalls

Product management had come a long way since the “Brand Men.” By the 1970s Product management principles developed by companies like Hewlett-Packard and Toyota were starting to see adoption by more and more companies, even if the product manager role was not. In many companies, for example, marketing had been given the task of getting the voice of the customer. Other tasks that should have fallen to a product manager, (or at minimum had their involvement), might have either been unattended to or assigned to varying departments.

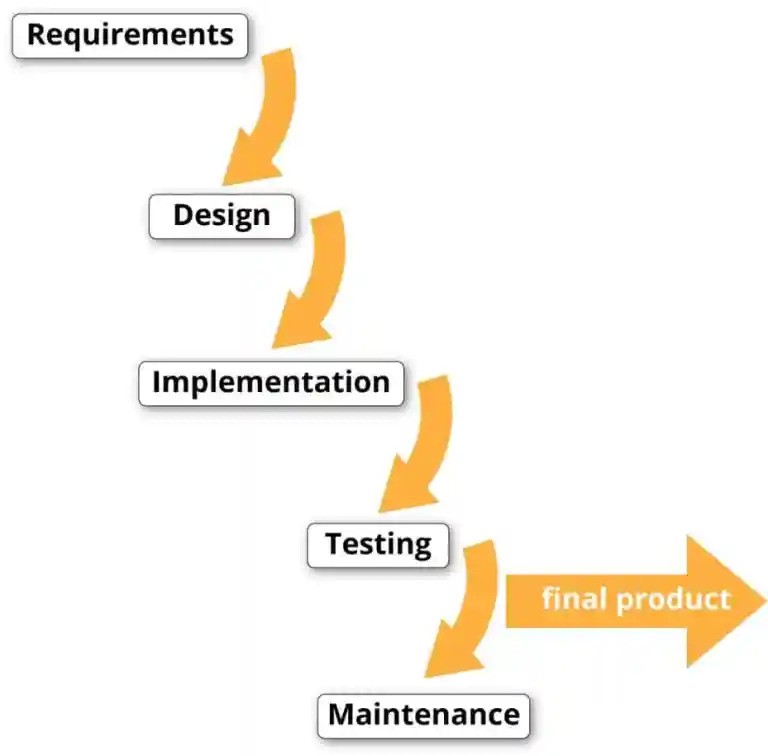

A key example comes in the form of the “waterfall” model. This model was supposedly introduced in the ’50s but became more popular in the 1970s when written about by Dr. Winston Royce in his paper, “Managing the Development of Large Software Systems.” As software development was slowly picking up steam at that time, Royce’s proposal was to create a very sequential model with cleanly delineated steps to ensure software was developed correctly, (Going from “requirements,” to “design,” to “implementation” for example). You cascade through the steps like going down a waterfall, but you cannot move on to the next step until the previous one has been completed.

While models like these might be a good start, by today’s standards it has proved to be slower and laborious. The problem at the time of its implementation was that there were few product managers to oversee it from beginning to end. As such, it often proved easy for different departments to essentially operate in silos while developing a product. It’s for these reasons and more that further innovation in the process would start to develop and take hold in the late 1980s.

You Rebel SCRUM

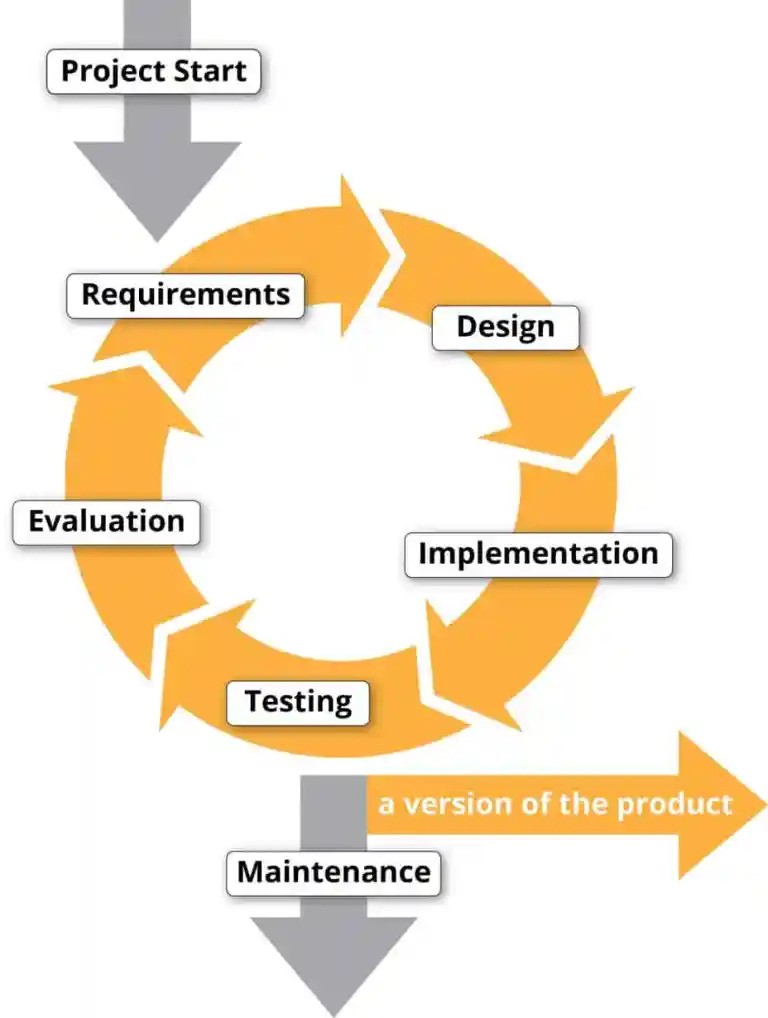

In 1986, an article in the Harvard Business Review called “The New Product Development Game” introduced a concept called “SCRUM.” The authors, Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka, made their case for a faster and more flexible way of developing products with this new concept. This proposed methodology stood out in stark contrast to the very sequential, step-by-step “waterfall” methodology that had been introduced to the product management world in the 1970’s.

Instead of a “sequential or “relay race” approach to product development” they argued for a “holistic or “rugby” approach—where a team tries to go the distance as a unit, passing the ball back and forth.” They had observed that companies in both Japan and the United States were already evolving to this better system as it “may better serve today’s competitive requirements.”

Borrowing the term “scrum” from Rugby, (short for “scrummage), Takeuchi and Nonaka laid out characteristics for “moving the scrum downfield” which included principles like “overlapping development phases” and “multi-learning.” The SCRUM framework caught hold in product management ranks, even if it did take a few years to take off. It was helped by experts like Jeff Sutherland and Ken Schwaber who added to the framework before creating a more formalized version of SCRUM in 1993 that would end up being heavily adopted by software development companies. It was about this time that the product owner role was also created.

Product management had come a long way in about 60 years, but even by the 1990s, product management jobs were not common. Companies like Hewlett-Packard had shown how valuable the product manager role could be but very few companies had created product manager roles of their own. That was until the internet changed everything.

The Web and the Need to Get Agile

About the same time that SCRUM was catching on, so too was the World Wide Web. In 1993 there were only 130 websites in existence. By early 1996 that number had exploded to over 100,000. By the year 2000, it was estimated that about 300 million people around the globe were on the Internet.

The exponential growth of the World Wide Web had resulted in the massive growth of tech companies. For example, Jeff Bezos founded Amazon in 1994, and by 1996 they had revenues over $15 million. A year later Amazon’s revenues neared $150 million and by 1998 revenues soared to over $600 million. Amazon, and all the tech sector, was growing at a rate that nearly no one could keep up with.

Software development specifically needed to move fast and furious. The methods and models in practice at the time were too slow to keep up with the pace of the market, which is exactly what led to a now-famous meeting of 17 software engineers at the Snowbird ski resort in Utah in 2001. These engineers came together with a single goal in mind: to make software development faster. Together these 17 engineers, (which included Jeff Sutherland and Ken Schwaber of SCRUM fame), created the Agile Manifesto.

The Agile Manifesto focused on taking the best parts of product management practices that had been developed over the preceding decades while throwing out the bad. The manifesto had 4 primary values:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

The engineers also established 12 key principles for Agile software development. The first principle hearkens all the way back to McElroy’s memo on brand men:

Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software.

What resulted from this meeting was principles and values that had been in place in many parts of product management had finally been formalized. Within Agile, frameworks like SCRUM and Kanban are still utilized to this day, but many organizations do so now around the guiding values and principles of the Agile Manifesto.

Agile has now been in place for 2 decades and clearly, it works. Studies have shown improved satisfaction of deliverables, and research by CA Technologies has shown that working teams, when dedicating 95% of their time to a single agile team, outproduce other teams by a 2:1 ratio. In other words, when followed, the Agile manifesto produces the results it was intended to.

Product Management Today

As much as the models and methodologies have changed over nearly 100 years, at the heart of product management today is what has always been at the heart of product management. Neil McElroy hit the nail on the head with his “Brand Men” memo when he stated that brand men should personally study to “find out the trouble” and “after discovering our weakness, develop a plan that can be applied to this…sore spot.”

New techniques will develop and evolve, and we will champion those techniques that produce the desired outcomes. But for now, let’s celebrate all those who got us to this point in product management history and say thanks, for helping us learn how to make better products, all by taking the time to understand your customer’s problems. Here’s to the Brand Men.