On this episode of Dear Strategy, we answer the following question…

Dear Strategy:

“How do you manage the lifecycle of mature products in resistive markets?”

I’m actually going to use this question to address something that’s been on my mind for quite some time. But more on that in just a bit.

First, let’s try to level-set on exactly what is being asked here. My interpretation is that we’re dealing with a product that’s been in the market for a long period of time, and that at least some portion of that market is resistant to moving away from the product for whatever reason. Based on this description, I’m also going to assume that the market we’re talking about here is in the business-to-business space; only because those are usually the types of marketplaces that are most likely to be resistant to change. So, with those assumptions in hand, let’s get into this discussion.

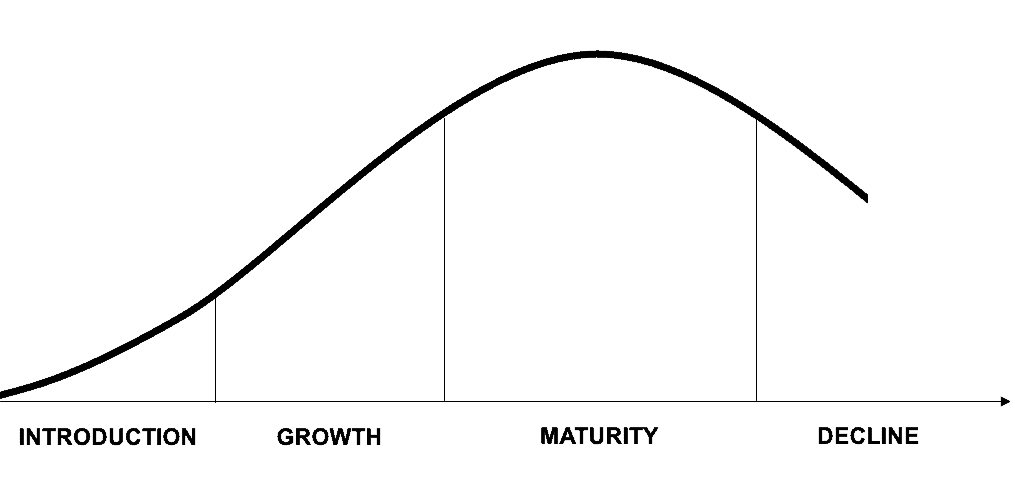

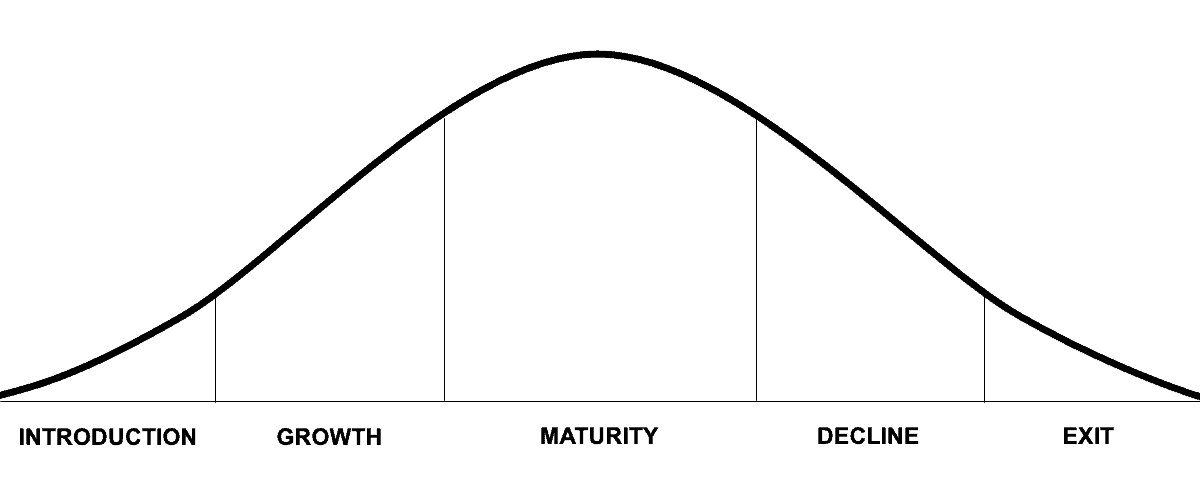

When we talk about a mature product, we’re usually referring to its place on the standard post-launch product life cycle curve. For anyone not familiar with that concept, the theory is that every product will have a finite life within any given marketplace. In other words, it will be introduced, it will grow, it will mature, it will decline, and it will eventually be exited from the marketplace. These stages are referred to as the product life cycle – which is typically measured in terms of revenue or volume; although many other metrics have been proposed along the way including market share, customer adoption, profitability, etc.

When you put all of that together and plot it out, the graphical representation usually looks something like what is shown below.

Now you may have noticed that I talked about 5 lifecycle stages (introduction, growth, maturity, decline, and exit), and yet the lifecycle curve shown above only has 4 stages to it. So what gives? Well, that’s a great question! And I really wish that I completely knew the answer! But, unfortunately, I can only surmise…

The version of the life cycle curve shown above is based on one that was proposed by Theodore Levitt in his article “Exploit the Product Life Cycle” written in the Harvard Business Review in November of 1965. To Mr. Levitt’s own admission, the concept of a life cycle curve had been around for many years prior, and the purpose of his article was simply to clarify and validate its importance. So this is the version of the product life cycle that became popularized – but, at least in my opinion, not without a few questions that I believe are worth asking.

The biggest of those has to do with why the decline stage is not drawn out to its logical conclusion which, assuming we are measuring revenue, would be the point of zero sales. There seems to be an informal consensus that, once a product enters into decline, companies have choices to make – any of which could drastically alter the shape of the remaining curve. Those choices might include retiring the product, enhancing the product, or continuing to stretch the decline stage as far as it can be stretched. So perhaps that’s why there’s no definitive end to the standard curve – because there’s simply too much variability as to what can happen to a product near the end of its life. And it is at exactly this point where the answer to our question picks up.

“There seems to be an informal consensus that, once a product enters into decline, companies have choices to make – any of which could drastically alter the shape of the remaining curve.”

When one is analyzing the life of a product, I suppose it makes sense that your life cycle curve would stop somewhere short of its logical conclusion because, if it were concluded, then, by definition, you would be analyzing a product that no longer exists in the marketplace. So from the standpoint of looking at where a product has already been, the currently accepted version of the life cycle curve makes perfect sense. However, if you are using the life cycle curve to plan rather than simply to analyze, then you may want to consider drawing out your curve based on where you think your product is going in addition to where it has already been. And that would involve the inclusion of an “Exit” stage, or some similar forward-looking view of how you want your product to move through the rest of its life. A curve like this would look something like what is shown below.

Taking this approach, you now have some options as to what you might want to do – especially if your product is already in decline. Perhaps you want to enhance your product and try to push it back up the curve (effectively extending your product life cycle). Or perhaps you want to discontinue your product and quickly move your customers to a newer version that is just about to enter the introduction phase of its own curve. Or perhaps, as might be the case in many business-to-business environments, you want to slowly exit your product from the marketplace, allowing ample time to prepare “resistive” customers for whatever changes they are about to face. The point is, drawing your life cycle curve out to some logical conclusion allows you to determine the fate of your product before the market determines it for you. And that should help eliminate some of the question marks around what to do with customers who simply don’t want to change.

Listen to the podcast episode

Dear Strategy: Episode 122

Are you interested in strategy workshops for your product managers or business leaders? If so, please be sure to visit Strategy Generation Company by clicking the link below:

Bob Caporale is the founder of Strategy Generation Company, the author of Creative Strategy Generation and the host of the Dear Strategy podcast. You can learn more about his work by visiting bobcaporale.com.

Bob Caporale is the founder of Strategy Generation Company, the author of Creative Strategy Generation and the host of the Dear Strategy podcast. You can learn more about his work by visiting bobcaporale.com.