Here on The Review, we’ve committed ourselves to an annual ritual each January — one that doesn’t involve resolutions, but rather, reflections.

This year marks one decade of using the first week of a shiny new year as a chance to revisit every article and podcast episode we published in the 365 days prior. From 2013 to 2023, the goal of this annual, well, review has remained consistent: to distill the standout tactics down into one actionable guide of advice. And over the years, we’ve found it’s a worthwhile exercise in more ways than one.

For starters, we hope this concentrated list of can’t-miss-takeaways is useful to our readers, as it both surfaces the stories you might have missed entirely and makes for a handy refresher on the ones that previously struck a chord.

But these collections also serve as something of a time capsule, highlighting the top-of-mind topics and the most resonant advice in a given year. For example, our 2020 edition focused on the shift to virtual work and the challenges of leading through a crisis, while last year’s compilation nodded to “the Great Resignation” gripping the headlines, as job-seekers pursued new opportunities, startups notched record-breaking valuations, and funding rounds came together at lightning speed.

It won’t be surprising, then, that 2022 certainly brought plenty to reflect on. Assembling this year’s list was a reminder of just how quickly things can change. Amid the layoffs, budget cuts and market corrections dominating the discourse, we strived to bring you the stories that would make a difference in your day-to-day — whether you’re a candidate considering early-stage startups for the first time, a founder looking to get to product-market fit more quickly, a manager looking to support your team through upheaval, or a leader readjusting your annual plan.

While many are feeling more uncertainty than ever about what the new year will bring, there are plenty of bright spots to balance out the scales. Innovation is taking place at a rapid clip, energizing entrepreneurs everywhere. Recent breakthroughs in fields as wide-ranging as AI, nuclear fusion and cancer treatment are bringing that spine-tingling excitement that feels like a peek into the future.

But oscillating between these extremes of innovation and uncertainty can be disorienting. So while leafing through our previous annual installments (from 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021), we were on the hunt for a common thread to serve as a compass in the months ahead.

Looking at the most popular advice we’ve shared over the years, topics seem to run the gamut — from the philosophy of delivering radical candor and the engine that powers product-market fit, to the counsel to give away your Legos or the charge to make speed a habit. And yet readers return to these articles year after year, whether they’re revisiting or stumbling across them for the very first time.

Here’s our hunch as to why: The best company-building advice shares a certain timelessness — and a focus on the fundamentals. Think of it like a pianist playing their scales or a pro athlete running drills. You can’t control what’s going to happen in the market. But you can control how you approach the nuts and bolts of company-building, managing, and personal growth.

That hardly means sticking your head in the sand and ignoring trends or what’s most useful in the near term. (So whether it’s frameworks for pressure-testing a new AI-startup idea, tactic-laden stories on finding market pull quickly, or playbooks for building with more efficiency, rest assured that we’ll have plenty up our sleeves this year to help you meet the moment.)

But it does require maintaining a certain level of perspective and focus. That’s why we also pledge to continue delivering enduring, evergreen advice on the startup essentials — no matter the climate.

With that in mind, for the tenth year running, we are grateful for the chance to repeat a familiar refrain: We hope you find relevance and resonance in the following roundup of the 30 best pieces of advice we published this past year. Take it with you into 2023 as you keep hunting for those bright spots — and stay focused on the fundamentals.

1. Add these question prompts for regular reflection for managers.

There’s plenty of content out there on the questions managers should be asking others, whether it’s (shameless plug for our own pieces of content) what to ask in a 1:1 with a direct report, questions to ask candidates in interviews, or questions to ask their own managers when managing up.

But there’s not nearly as much advice on the questions managers should be asking themselves regularly during key moments of reflection. So we sent out a call to leaders in the First Round community to crowdsource some ideas. The full list made for our most-read article of the year, but here are a few highlights:

- Who haven’t I heard from? “It's easy to think, ‘That person is so strong, they just take care of themselves. I'll go focus on the rest of my team.’ But I firmly believe that the majority of my time and coaching energy should actually go into people who are high-performing,” says Molly Graham, former COO of BloomTech.

- Does the team know what the strategy is? “To be a successful manager, you can’t just rely on doing it all yourself. You have to teach your team to think strategically. If you only accept or reject their ideas, your team never learns how to improve their judgment,” says Wes Kao, co-founder of Maven.

- What resource recommendation can I send someone this month? “I aim to send my team members one article, podcast or book recommendation every month. It’s been a great tool for opening up dialogues on various topics that we may not get to otherwise,” says Colleen McCreary, former Chief People Officer of Credit Karma.

- Have I asked for help lately? “Lack of delegation and an inability to understand where you truly add the most value can derail meaningful growth opportunities for your team, cause unnecessary burnout and stress, and ultimately impact how well your company scales,” says Massella Dukuly, Director of Team Enablement for LifeLabs Learning.

- Was I busy or productive today? “In a startup environment, it’s easy to be very busy, but the real challenge is finding ways to be truly productive in your work,” says Lattice’s Brett Wienke.

2. Start with the monkey — not the pedestal.

When First Round partner and co-founder Josh Kopelman first read Annie Duke’s bestselling book, “Thinking in Bets,” he was intrigued by how we could apply her frameworks to our own work of “betting” on founders. (In case you missed it, last year, we were proud to announce Duke as our Special Partner for Decision-Making Science.)

So it’s safe to say that we were eagerly anticipating the release of her brand-new book “Quit: The Power of Knowing When to Walk Away.” In her latest project, Duke makes the case for why we need to get better at quitting — a touchy topic for founders, who often worship at the altar of perseverance and grit.

“The problem is that the grit that allows us to power through will also get us to stick to things that aren’t worthwhile,” says Duke. “Success comes from sticking to the stuff that’s working and quitting the rest. That’s why you need to understand whether or not you should continue as quickly as possible.”

To get there faster, she recommends leaning on this technique from Google X’s Astro Teller: “Imagine that you want to train a monkey to juggle flaming torches while standing on a pedestal in the town square. Teller says to tackle the hard part first because everything else is just going to create an illusion of progress,” she says.

“In other words, don’t start by building the pedestal first. Instead, make sure that you can actually train the monkey to juggle the flaming torches. That's the unknown, the bottleneck. You can certainly build a pedestal later — in a pinch, you could turn a milk crate upside down,” she says.

“But if you start with the pedestal, the time, effort and money you put into building it will start to create sunk costs. Now your identity is more wrapped up in what you're doing — even though it's not creating true progress — making it much harder to actually quit when you figure out that you can't get the monkey to juggle those torches,” says Duke. “Instead, you’ll press on, saying, ‘I just need to do this one more thing, I'm so close to the breakthrough.’”

That’s why you should be extra wary when you hear phrases like “Let’s start by tackling the low-hanging fruit,” at a project kickoff or strategy session. “Make sure you're not just collecting debris without actually solving for the hard thing first,” says Duke.

There’s no problem with tackling low-hanging fruit. Eventually, you have to. But you better make sure that you solve for the bottleneck first — because every bit of low-hanging fruit you tackle creates an illusion of progress and sunk cost problems.

3. Put your own annual reviews in place (and treat them as bug reports).

To scale your leadership alongside the company, you’ve got to arm yourself with a steady stream of feedback — which can be hard to come by as a founder. That’s why from the early days of HubSpot, co-founders Brian Halligan and Dharmesh Shah invested time in running each other’s annual reviews.

Here’s how the process works: “Whoever is doing the review picks 15-20 people to give feedback on how things are going. It’s the review writer’s responsibility to then synthesize all that feedback, add their own assessment, and then write a 10-15 page review,” says Shah.

After presenting the evaluation packet, the recipient is given space to respond in written form:

- Here’s what I heard from the feedback

- Here are the things that I’m going to tackle over the next year.

- Here are the things I’m not tackling.

That last one may not be expected, but it’s a critical piece of the puzzle. “I often received feedback that folks didn’t see enough of me at the office. My response has always been that this works as designed. As a super-introvert, two hours of in-person time will zap my energy for the rest of my day,” says Shah. “If you choose not to tackle a particular bug, it’s important to explain why.”

Here’s an example of a bug he did take on: “I had heard that folks didn't really know what I’m working on or what I cared about,” says Shah. To tackle this bug in an introvert-friendly manner, he started a series of internal blog posts called “Dharmesh’s Ponderings.” “I cover all sorts of things I wouldn’t talk about publicly. Folks can opt-in to read a blog post about what I think about web3 or why we made a particular decision for the company,” says Shah.

4. Play in arenas, not your own backyard.

As a startup founder, Phaedra Ellis-Lamkins has received heaps of advice while building Promise. But one of the most resonant pieces of guidance came from earlier in her career, when she worked with Prince (yep, the musician). Here’s how Ellis-Lamkins recalled the story when she joined us on the In Depth podcast:

“When I worked with Prince, one of the issues was that there was financial stuff that had to be cleaned up. So I spent a lot of time having conversations with people who just wanted to spit in my face and thought I was the biggest jerk ever. I knew I was doing the right thing, but it hurt my feelings,” she says. Ellis-Lamkins called up Prince one day, and he imparted a bit of wisdom that still guides her:

You have to decide if you’re going to play in Madison Square Garden or in your backyard. Because no one boos you in your backyard. But if you play in Madison Square Garden, someone’s going to boo you.

“I think about that a lot as we build Promise, because we do both wrong things and right things. And I remind myself that as long as we're acting with integrity, I just have to get used to boos. Because the impact I want is Madison Square Garden — not my backyard,” says Ellis-Lamkins.

5. Set goals after the roadmap — not the other way around.

The corporate landscape is littered with jargon that’s all but lost its meaning from overuse — think “net-new,” “low-hanging fruit” or “boil the ocean.” Right alongside this graveyard of oft-repeated business-speak? Strategy.

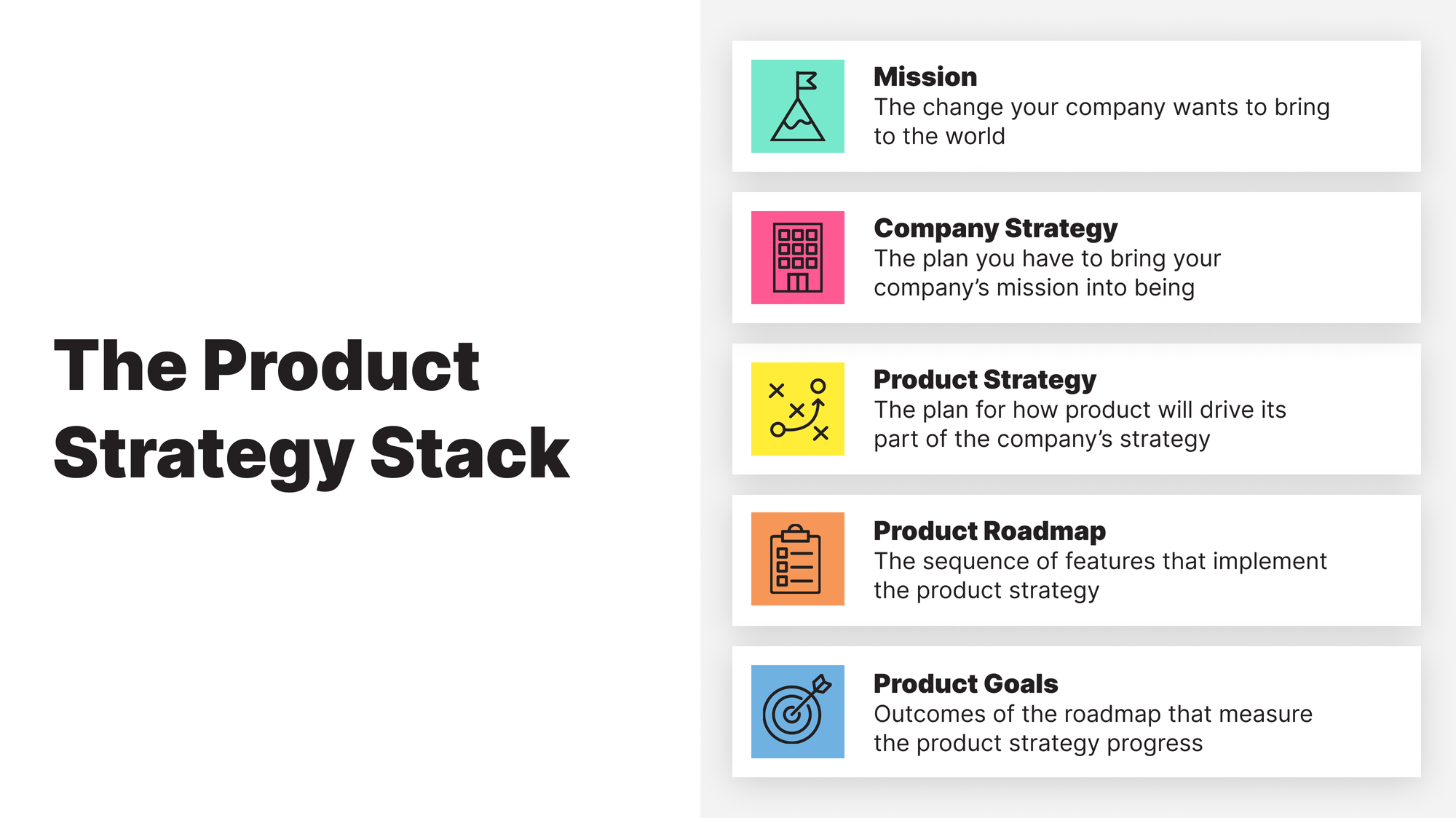

As a product leader (formerly at Tinder and TripAdvisor) and current co-founder of Outpace, Ravi Mehta’s made it his mission to crisp up what it really means to dive into product strategy. He teamed up with Zainab Ghadiyali to create the Product Strategy Stack, which encapsulates the company mission, company strategy, product strategy, product roadmap, and product goals — bringing these amorphous ideas like “mission” or “vision” into sharper focus. (The message clearly resonated — Mehta’s appearance on our podcast In Depth was our most popular episode for the year.)

Mehta’s strong recommendation is to move through each piece of the Product Strategy Stack in order. “Goals are at the bottom of the stack, not at the top, because goals should come from the roadmap — not the other way around. But more often than not, companies say our goal is to increase retention by 10%, and then the team will develop a roadmap to try to achieve that goal,” he says.

He leans on a favorite analogy to (in a sense) drive the point home. “Let’s say we want to go on a road trip from Los Angeles to Las Vegas. One of the goals or KPIs that we'll have on that trip is the number of miles driven — but that's not sufficient in and of itself for us to reach our destination,” he says. “We can drive 200 miles in the right direction — but we can also move in the wrong direction. In both cases, we've achieved our goal, but we haven't necessarily made progress on the ultimate outcome that we wanted — which is to get to Las Vegas.”

6. Protect your team’s time, even when they won’t.

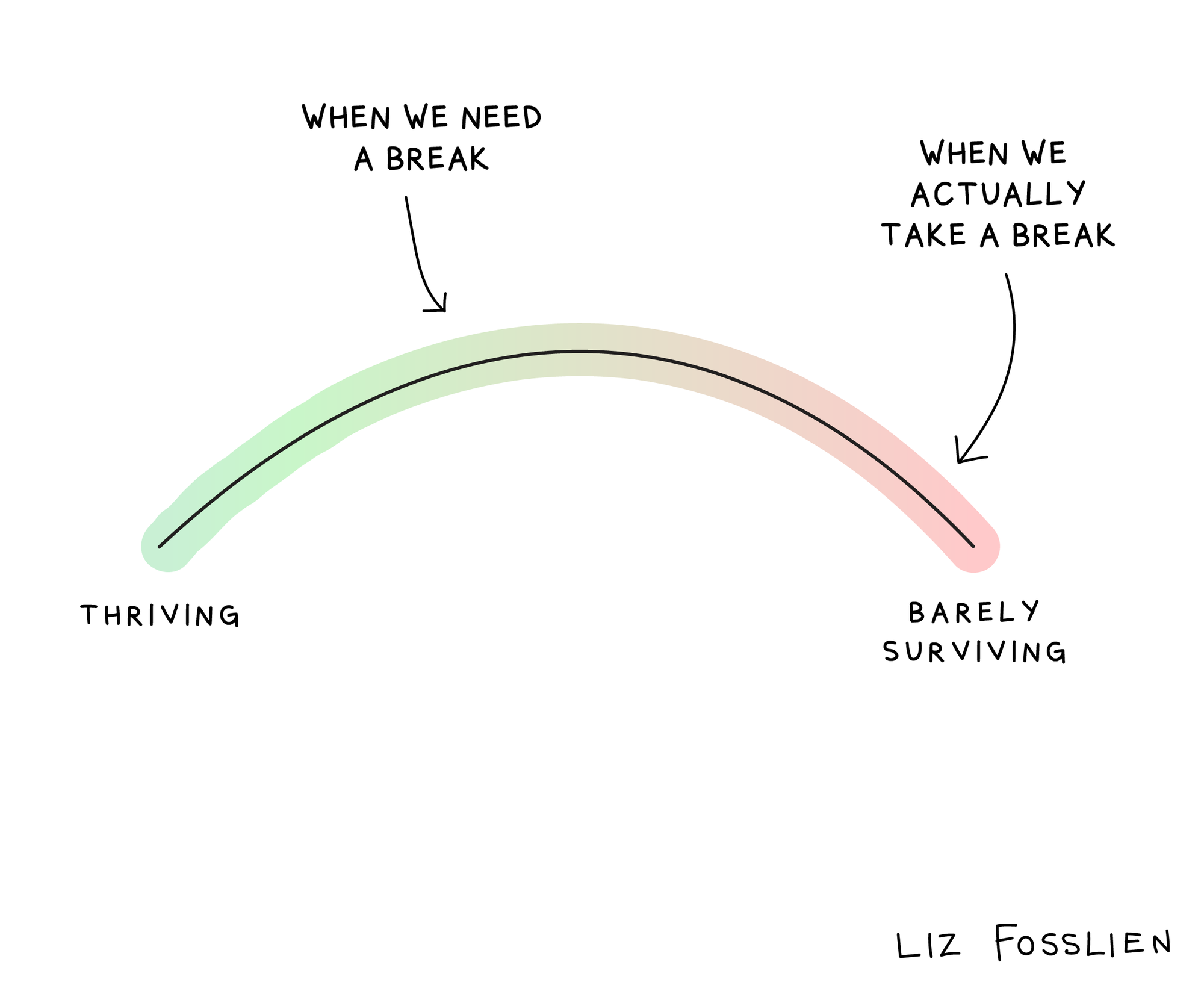

We’ve all felt the symptoms before. Saying yes when you are already at capacity. Feeling so overwhelmed that you start to cut out activities such as exercise or alone time. Getting the Sunday scaries — on Saturday. After spending the better part of the past decade studying teams, meeting with experts and researching the science behind emotions on the job, Liz Fosslien has become an expert herself on recognizing the warning signs of burnout. (She explored this topic in “Big Feelings: How to Be Okay When Things Are Not Okay,” her second book with co-author Mollie West Duffy.)

It can be difficult for folks to muster the courage to ask for a break, which is why Fosslien says managers must keep an eagle eye out for burnout on their team.

Saying you want your people to have a healthy work-life balance is great, but if their calendars are filled with back-to-back meetings, and they get pinged at all hours of the day, chances are they won’t feel safe taking the breaks they need.

Encouraging a culture of rest takes regular practice. For example, to protect an employee’s vacation time, consider reprioritizing projects they are a part of, or jumping in to finish something while they’re out. Treating the little things with the same attentiveness as life’s biggest hurdles will go a long way.

7. Evaluate early-stage startup opportunities thoughtfully.

Candidates looking for new roles find themselves competing in a tighter job market as hiring freezes spread and uncertainty swirls. Understandably, many job-seekers may be in a mode where a new role at any company sounds promising. But if you can take a beat, widening the aperture of your search and being as thoughtful as you can be about your next opportunity is of critical importance.

However, particularly for candidates coming from larger, more established companies, evaluating the outlook of and potential fit with a startup is a daunting prospect. So we asked experts in the First Round community for their advice on what to look for when evaluating a role and the prospects of an early-stage company. The full list of tips is worth bookmarking, but here’s a quick preview:

- Think like an investor. “Working in smaller startups is investing your time — which is the most invaluable thing you have. When considering an early-stage startup role, ask yourself: Would you invest your own money into this company and this founding team?” says Vishal Kapoor, VP of PM and PMM at Affirm.

- Become a student of not just what makes a great product, but what makes a great business. “Sometimes a flashy product or idea can be quite catchy, but even at an early-stage startup, understanding the revenue model is exponentially important,” says Alexis Zhu, Head of Payments Partnerships at Stripe.

- Embrace the opportunity to contribute beyond your immediate job description. “There are some 'milestones' in a big company role — people management, promotions, org size or scope — which simply don't translate into early-stage startups. It's important to be open-minded about success looking different at smaller companies," says Lauryn Isford, Head of Growth at Airtable.

8. Get customers to your product’s “magic moment” faster.

In the earliest stages of company-building, folks often worship at the altar of speed — launch an MVP quickly, gather customer feedback and start pivoting their way into product/market fit.

But the path to building Figma was an exercise in patience. Founded in 2012, the design startup didn’t actually start shipping software to beta users until 2015. After launch, it took another two years to add paid pricing tiers.

The full story tracing their early GTM path makes for a fascinating read, but we’ll focus on one particular detail here: When layering on pricing with its freemium model, the decision on what to gate at Figma’s paid level took a bit of trial and error. “The first time around, we wanted to gate the features you need for a design team, versus what you need as an individual designer. So in the first iteration of Figma’s pricing model, the free tier limited you to only two users collaborating on a file together, but you got unlimited projects. And in the paid tier, you could have many more folks collaborating on a single file,” says Claire Butler, one of the company’s first 10 employees and its first business hire.

But this initial strategy wasn’t quite working — and, as Butler explained on the In Depth podcast, it goes back to the early team’s intuition on Figma’s secret sauce. “By limiting the number of folks who could collaborate on a file in the free tier, we weren’t enabling people to experience the magic moment of multiplayer collaboration,” she says. So the team flipped the script. “We reversed it so that in the free starter tier, you could only have a couple of files, but you could have an unlimited number of people collaborating in that file.”

When you think about gating your product, consider how you can funnel customers toward your magic moment and get them to experience that as quickly as possible.

9. Draft up a personal press release.

“At the end of the day, the only thing that actually matters is the impact our work has on our company, our customers, our colleagues, and our professional development. And the only way to stay on top of that is to hold ourselves accountable to our higher-order goals with as much enthusiasm as we have for the dopamine rush of reaching inbox zero.”

Brie Wolfson has worked for tech companies of all shapes and sizes, including household names Figma and Stripe, so we’d recommend listening to her on this one.

These days she’s got her hands full building Constellate, but last year, Wolfson took the time to share her personal collection of docs and templates for staying focused in the day-to-day, while still making progress towards broader goals longer-term. There’s so much tactical goodness to be found that we highly recommend borrowing her toolkit in full (and subscribing to this calendar to incorporate these exercises into your workflow).

But we’ll highlight one particular template here: As a quarterly exercise, Wolfson suggests sitting down to write a press release — not about a new product launch, but about all the things you shipped and the impact they are having.

Whether it’s part of performance review season or you’re looking to engage in deeper reflection as the new year gets underway, the timing couldn’t be more perfect to take this one on. Here’s her suggestion on what to include (and a handy template for crafting your own):

- Headline/Lede: the attention grabber

- One-line summary: imagine how someone would describe this to a colleague

- Top 3-5 things you shipped

- Where your time went

- Key insights or learnings

- Progress on metrics

- Qualitative impacts

- Contributions to the broader team/company

- Feedback you received from stakeholders/users (internal or external)

- One piece of art (graph, picture, screenshot, etc.)

- Overall mood/sentiment

- Anything the broader organization did that you wish you could have been a part of

- What you’re really proud of

- Anything you’re not so proud of

- A look ahead: What you’re shipping next, what you’re excited about, big opportunities for you, your team, or your company, and any foreseen blockers, risks, or things you’re worried about.

10. Coach, don’t fix.

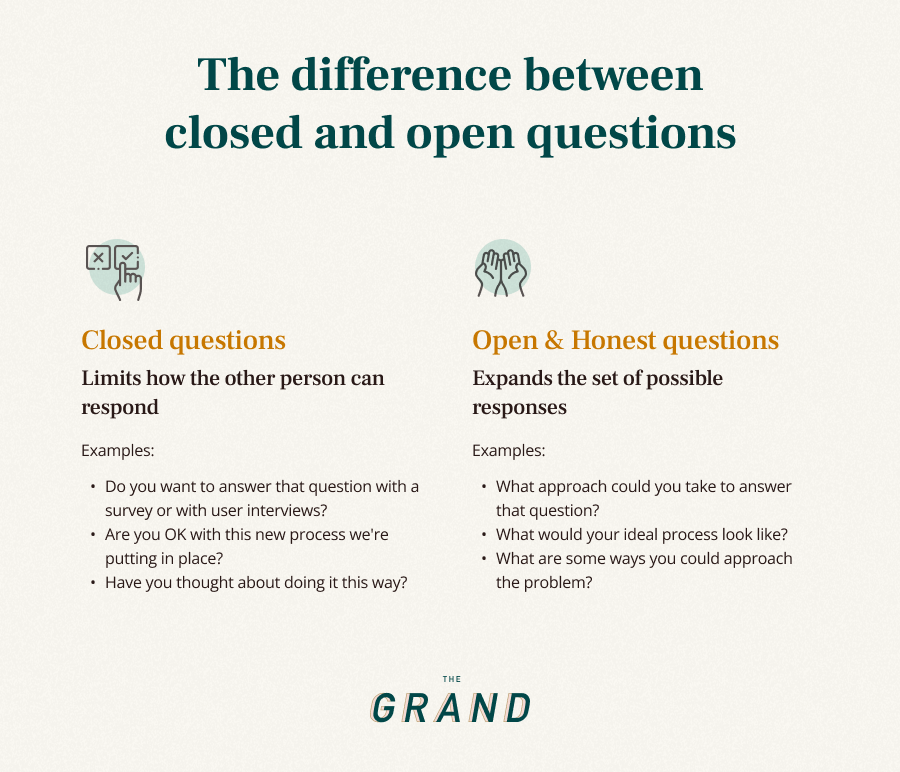

“As managers, our default setting is to jump in and fix things when a situation goes sideways. ‘I know the answer, and I need to tell them,’ is a common mentality. But over-relying on fixing constrains our ability to lead and robs our team members of growth opportunities,” says Anita Hossain Choudhry and Mindy Zhang, who’ve coached hundreds of executives via The Grand and Throughline.

They’ve observed that the biggest tension for managers happens when we use our “own compass” to guide our team — or rather, rely too much on our own past experiences to advise direct reports through their unique challenges. “Being the hero who swoops in and relieves someone of their problems feels good, and it’s hard to let go of the chance to reinforce our competence,” they say.

Instead, Choudhry and Zhang advise putting on your coaching cap. “To put it simply: Coaching is a skill, while being a manager is a role. The key element is that you’re trying to tap into their wisdom, not yours.”

Two foundational skills they recommend for getting started are practicing empathetic listening and asking open and honest questions. Start by shifting from the more natural self-focused listening mode (“What does this mean for me?” or “How do I help them figure this out?”) to empathetic listening (“What's going on for this person?”). Next, watch out for a tendency to ask closed questions like, “Have you thought about doing X to solve the problem?” which limits the set of possibilities for the other person to respond with. (Choudhry’s and Zhang’s handy chart below offers up some other alternatives.)

11. Test out an anti-pilot to eliminate busy work.

As a four-time founder (and current CEO of Levels), Sam Corcos is relentless about optimizing his time. Far too often, he sees folks reluctant to delegate as they transition from builder to leader — but it’s one of the most critical skills to get right.

“In ‘The 4-Hour Workweek,’ one line from author Tim Ferriss stuck out to me: ‘Never automate something that can be eliminated, and never delegate something that can be automated or streamlined. Otherwise, you waste someone else’s time instead of your own, which now wastes your hard-earned cash,’ says Corcos.

Here’s a tactic he leans on to eliminate busy work, rather than delegating to support staff or using engineering time to automate it:

Before you consider delegating or automating a task, it’s always worth interrogating whether that task is worth doing in the first place. There’s nothing worse than spending time improving something that should never have existed to begin with.

A tactic to try is the “anti-pilot”: removing the feature and seeing if anyone notices. “If you don’t get a lot of complaints, it’s a strong indicator that the feature wasn’t adding as much value as you thought,” says Corcos.

“A recent example is when I considered adding a recurring task for an EA to remind people to put together a weekly recap for their function (which takes about 2 hours). But instead, I asked the functional leads to refrain from posting their updates for a couple of weeks to see if anyone noticed. It turned out that it was a nice-to-have, but really didn’t add that much value, so we killed that project,” he says.

12. Deepen the conversation to avoid doorknob comments.

Ximena Vengoechea is a master in the art of listening. As a seasoned user research leader, she’s led and observed thousands of interviews at companies like Pinterest and LinkedIn. She’s even written a book on the subject, publishing “Listen Like You Mean it: Reclaiming the Lost Art of True Connection.”

One area that’s ripe for refining your listening game is the standard 1:1 meetings between managers and direct reports — mainly because it’s easy to fall into a familiar rhythm here.

“As you build a relationship with your direct report over time, it’s important to pay attention to patterns. For example, in therapy, clients often bring up the most important thing in the final few minutes of a session — it’s called a doorknob comment. Right before you start wrapping up, you say the thing that you actually wanted to say the whole time, but needed the entire hour to muster enough courage. And we sometimes see a similar thing in 1:1s,” says Vengoechea.

Ending conversations on a doorknob comment means that these discussions never stray too far from the surface, and the uncomfortable challenges are left unexplored.

If you’re a manager looking to deepen the conversations you’re having with your direct report, try asking this one question: “What would you save for the end of our 1:1 today? Let’s start with that.”

On the flip side, Vengoechea encourages direct reports who are struggling with feeling heard to consider using clear and simple language to be as direct as possible with managers. “Often, we think we are expressing our needs clearly and we're actually talking around them. The most direct path to being heard is to communicate our needs explicitly.”

13. Share interview questions with candidates in advance.

Co-founders Amber Madison and Liz Kofman-Burns structure their hiring process a bit unconventionally. Before every interview, candidates for Peoplism, a data-driven DEI consulting firm, receive a prep guide outlining the hiring timeline, salary — and the questions they’ll be asked in the interview.

The thesis behind this atypical approach is to make their interview process as inclusive as possible, given how many behind-the-scenes factors contribute to someone nailing on-the-spot interviews.

“Being great in an interview setting can be the product of going to elite schools, knowing people in the same profession, or even having access to someone who is already working at the company to prep beforehand,” Kofman-Burns says.“On-the-spot interviews evaluate a certain set of criteria — but is that the criteria that you’re really looking for in the role?”

If you want to evaluate candidates for clear competencies, you want to give them the best shot of actually showing you whether or not they have those skills. If you don’t give candidates a sense of what you’re going to be probing, you end up hiring folks who are just the best at interviewing.

Giving folks time to prep for the questions in advance also taps into what it’s actually like operating in most startup roles. “The way we set up the interview mirrors the real world, where you’re able to actually prepare for what you’re expected to accomplish,” says Madison. “When you give folks the opportunity to review the interview questions in advance, it raises your expectations of the quality of the answers you get back.”

14. Make sure you’re brushing and flossing as a manager.

As if you didn’t get enough grief already from your dentist, Russ Laraway has one more thing to add to your to-do list: practice managerial hygiene.

In his book published last year, “When They Win, You Win,” Laraway shares lessons he’s collected after two decades of managing people in several different environments (as an executive at Twitter, Chief People Officer at Qualtrics, a startup founder and a company commander in the U.S. Marine Corps, to name a few.)

In his research, Laraway found that reminding your team of company goals (and connecting the dots with how their work is contributing to them) is closely aligned with higher employee engagement. It’s also something that managers have to work on regularly.

To kickstart good habits, incorporate these tips in your next meeting:

- Set a cap on priorities to provide clarity. Ask each team member to articulate their three priorities — and be really strict about sticking to three. “Don’t let this turn into an arms race where someone starts listing four, and another then lists seven. This exercise isn’t about getting visibility into every single thing folks are doing. This is about doing the hard thinking about the most important thing folks need to get done today or this week,” says Laraway.

- Add this phrase to your repertoire to continue to bang the drum of what matters most. “Ask the question: Which quarterly goal does that workstream support? If you keep finding that the work that you’re doing isn’t reflected in the quarterly goals, it’s time to rethink how you’re approaching those OKRs, or get them right the next time,” Laraway says.

15. Try these lightweight tactics for gathering feedback — without infecting the group.

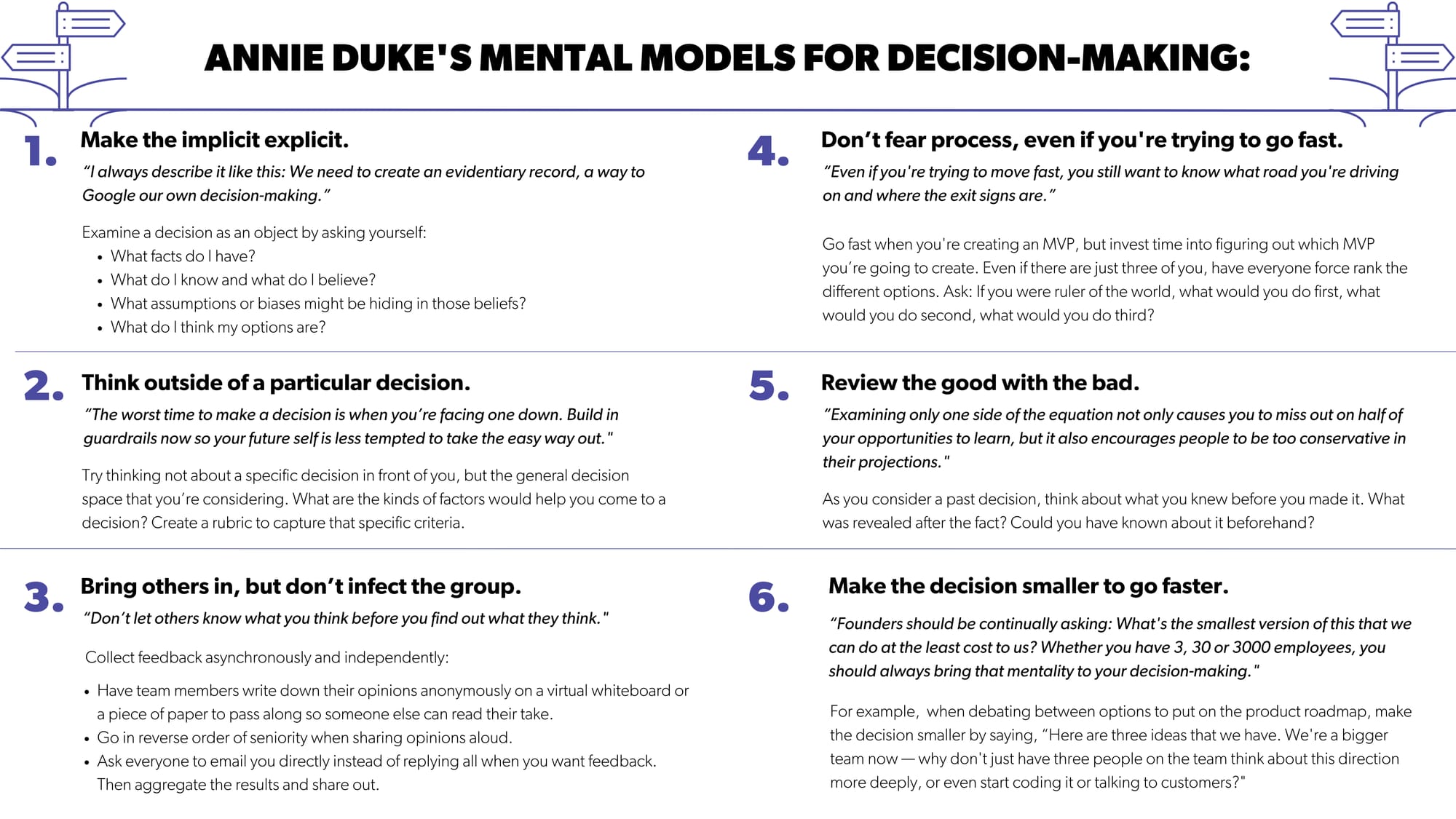

On top of helping us reduce bias and bring even more rigor to our own investing process, Annie Duke also shares her advice with founders and angel investors, both in closed sessions for the First Round community and in this tactical decision-making guide on The Review — so we’d be remiss if we restricted her to just one tip on this list.

There were so many excellent mental models (summarized in the chart below), but we’ll focus on number three: getting group feedback in an unbiased way.

“It’s great to have other people make the same judgments as you to uncover where there’s dispersion of opinion— but that only works if the judgments are independent,” says Duke. “In a group, people are going to try to convince each other. There’s going to be contagion, and sometimes it can even become combative, which is bad for decision-making.”

That’s why it’s critical to collect feedback asynchronously and independently. “That way, you can see everybody's opinion and pinpoint the places where opinions don’t align. I prefer to use ‘dispersion’ over the negative connotations of ‘disagree’ — it’s a more neutral way of talking about places where people’s opinions differ,” she says.

Here are a few tactics to try out:

- Have team members write down their opinions anonymously on a virtual whiteboard. Or if you’re in person, have them write it on a piece of paper to pass along so someone else can read their take.

- If folks on your team are sharing their own opinions aloud, go in reverse order of seniority.

- When sending an email asking for feedback on an idea, ask everyone to email you directly instead of replying all. Then aggregate the results and share out.

16. Check references on references, and listen for ownership language.

As the founder of people management platform Lattice, Jack Altman certainly knows a thing or two about powering successful teams. On In Depth, he shared tactical advice for assembling executive teams in particular — a challenge that never fades, whether you’re in the earliest stages of figuring things out, or the later stages of scaling the business.

“I've heard the analogy that building your company's leadership team is sort of like painting the Golden Gate Bridge — by the time you get from one end to the other, you have to go back and start repainting because so much has changed,” he says.

Here are two of Altman’s tips for making sure you find the right fit:

- Listen for ownership language: “This is one of those trite things everyone talks about, but you really do need to find leaders with a deep ownership mentality. That mindset comes through in the language people use and what they focus on when answering interview questions,” says Altman. “In their last one or two roles, I like to dig in by asking things like, what were you brought in to do? How did it evolve over time? Tell me about some of the big projects. What were the biggest successes you had? What were the things that didn't go the way you wanted? Just continuously asking why and what, pulling on those threads many, many times. Are they self-reflective about what they’ve learned, or is there a mentality of, ‘We didn't have the budget,’ or ‘The founders were setting things up for failure’?”

- Check your references: “I spend a lot of time on references, leaning on them pretty extensively. But you have to take things with a grain of salt. And sometimes you have to — this will sound a little crazy — do references on the references, like when you get a confusing reference where you can't piece a story together,” says Altman. “There are cases where I've done a reference with another founder about an exec candidate, and it doesn't make sense to me because every other reference was good. But after doing references on the references, I learned that maybe that founder was a difficult personality, or the candidate was actually being super respectful when they were describing how they left the company.”

17. Laser-focus on your ideal customer profile.

As a first-time founder just starting out, it can be challenging to pivot from architecting the product to developing a strategy for selling to customers.

Before joining First Round, Meka Asonye cut his teeth at Stripe as it scaled from 250 to 2000 people and matured its sales org. He later served as VP of Sales & Services at Mixpanel, running a 100-person global revenue team, so he’s the perfect sounding board for more technical founders who are just dipping their toe into founder-led sales.

Too often, Asonye sees founders trying to chase too many folks at once with their product. “The common failure mode I see is someone just wants to get to five customers, or a founder is eager to hit $100,000 in ARR, so they are having a conversation with everyone under the sun,” Asonye says.

I’m always telling founders I work with to do less, or do more for fewer people. Get to the red-hot core of who you believe your customer is, and you can work your way out from there.

So in the early days, go narrow, not broad, with your ICP (ideal customer profile). “Founders should be able to say what their customer looks like, where they hang out, what problems they have, how big their company is, and how you are going to sell to them,” Asonye says. “You can have a beautiful product, but if you are selling it to the wrong audience, it’s going to look like you have a horrible one.”

18. Give feedback like an Olympic coach.

“When you’re a high performer, the extent of the feedback you typically receive is, ‘You’re doing great!’ And while that makes you feel good in the moment, it’s not actually helpful in the long term,” says engineering leader Amber Feng, one of the first dozen hires at Stripe.

“I think about if I was an Olympic gymnast or an NBA basketball player and I asked my coach how I was doing. If all they told me was, ‘You’re doing great!’ I’d probably fire them. Your entire job as an elite coach is to give brutally honest feedback — tell me what I can do to improve, even incrementally.”

We want to be world-class Olympic athletes in what we do — and we need brutally honest feedback to get there.

When it comes to doling out impactful feedback for high performers, on the In Depth podcast Feng recommended starting with the report’s career goals. If you don’t know what folks are hungry for, you’ll struggle to give them useful feedback. “If I have a star engineer on my team who wants to become a founder, all of a sudden, I have so many ideas for them. The feedback probably won’t only be about improving their code quality — it will also be about what they can do to take on more leadership with one of our big business lines,” she says.

19. Dig deep into the business model, not just the initial idea.

Before starting Maven, Gagan Biyani co-founded Udemy (an online education company), started Sprig (a meal delivery startup), and was early at Lyft. Regular readers might also recognize his name from the incredible Minimum Viable Testing framework he shared here a few years back. Building on this alternative approach to the traditional MVP process, he stopped by In Depth last year to share a preview of the company formation advice in the ideation bootcamp course he runs with Sam Parr.

“One of the more common mistakes entrepreneurs make when starting a company is failing to consider all of the various business models before deciding which one to pursue,” says Biyani. “It sounds very simple. But it's amazing how many entrepreneurs start a company with a business model already baked in from the beginning.”

Take the more specific idea of a peer-to-peer marketplace for gardening supplies, with folks renting unused supplies to their neighbors. “I can take that idea and split it up into five or 10 different ideas. What if instead of renting, you’re selling them? What if I offered a rental service where you can rent gardening equipment from a centralized location? What if it was a gardening equipment e-commerce company? What if I decided to invent better gardening equipment than what exists today?”

If you don't think through all those different factors, chances are someone out there in the marketplace of ideas is going to come up with the right answer — but you didn't spend the time to figure out all of the options, so you were dead on arrival from day one.

Here are his suggestions for whittling down your list: “TAM is obviously one of the biggest drivers of whether or not you have the right business opportunity. Another way is to consider which one's the easiest to get started tomorrow — it's not enough, but it's helpful,” says Biyani.

“But another way is if all three ideas existed, which one would win in a competition? While I was right about the food delivery market with Sprig, we picked the wrong model. Sprig was a better experience than DoorDash or Postmates for a long time, and we were gaining market share — until Uber Eats came in and fast-forwarded our eventual demise. Our business was working when competitors were essentially unoptimized and not at maturity yet. What I didn't ask myself was what's going to happen 10 years from now when their business is working? And it's the best version of their customer experience as opposed to their current version? How is that going to compete with my idea?”

20. Revamp your manager training and ditch the dreaded role-playing exercises.

It’s possibly the most dreaded part of any leadership training — grab a partner and act out a scenario that demonstrates some management tactic, like giving difficult feedback to a direct report. In addition to being just plain awkward, Melissa and Johnathan Nightingale, founders of Raw Signal Group, don’t find role-playing to be of much use.

shitty

Instead, the duo advises creating a space where managers feel safe talking about the actual struggles they’re having. Here are two tips for laying the groundwork for vulnerable, impactful conversations:

- Set up the space: “We’re big fans of Priya Parker’s book, ‘The Art of Gathering,’ including her model for setting rules of the space. That includes clarifying what confidentiality means in the session and asking everyone to commit to it. This creates a safe space where folks can show up differently than in their day-to-day,” says Melissa.

- Go first: “The research is pretty clear that there’s reciprocity to vulnerability — they’ll go deeper when their colleagues do,” says Johnathan. “For example, I often tell the story about the first time I had to fire someone and how I got so stressed out that I threw up in the parking lot afterward.”

21. Sidestep the PMF pressure to launch quickly.

The early days of any startup seem like a mad dash to get a rough version of the product out into the world as quickly as possible. Andrew Ofstad and his co-founders certainly felt this pressure back in 2012 when they were tinkering with the idea that would go on to become Airtable. “At the time, it was all about the Lean Startup, getting early customer validation and failing fast, putting out a super rough prototype to get to know the customer and then quickly pivot,” he says.

Instead, they focused on tackling the main risk for the company as early as possible. “For us early on, that was, ‘How do we actually make this database accessible to non-programmers?’” says Ofstad. “That meant it was all about making it easy to use, iterating on a prototype and getting lots of feedback. It seemed like launching the product publicly wouldn't really get us more data or accelerate the path to our goal. We had to separate the concept of trying to get feedback from customers and refining the product from the concept of a public launch.”

Here’s what that looked like for Airtable: “Our strategy was to build a very horizontal product and then roll it out to more people over time. Very early on, we had a private alpha. It was invite-only, but you could refer other people, so that helped us get some organic growth, but not a ton,” says Ofstad. “After maybe 100 people or so, eventually we felt like we were in a good place.” This took two years, he says, which is why it’s key to loosen your expectations around what your MVP “should” look like. “We had to build so many features to get to something useful. The MVP for our product was not any one thing.”

22. Stop decisions from drifting around the org.

“The key thing that leads people to feel like companies are slowing down is when decisions don't get made., when there is an opportunity or an issue and it just drifts on. Not knowing who can make a decision is the curse of large organizations,” says Sara Clemens, former COO of Twitch.

At large corporations, making decisions is often not a matter of getting somebody to say yes, it’s getting nobody to say no.

As she explained on the In Depth podcast, as a startup begins to scale beyond a small group of founders and early employees, folks must sketch out decision rights to stay agile: “As COO, my role was to diagnose where there were decisions that were not clearly allocated to someone in the business. What I mean by decision rights is just literally who can decide the thing? Who can decide whether that can be funded? Who can decide whether or not we are going to review a customer query and make a change in policy based on new information? Who can decide whether we do a marketing campaign in Brazil?” she says.

23. Apply the Cinderella test to sharpen your messaging.

Arielle Jackson has had a hand in shaping hundreds of startup brands, whether it’s helping companies like Patreon, Loom, Bowery and eero architect their positioning and branding behind the scenes, or her previous product marketing work launching and growing marquee products like AdWords, Gmail and Square Stand.

She shared heaps of branding advice on The Review last year, but we’ll focus on one of the more common positioning pitfalls she’s observed: founders’ tendency to emphasize their product’s emotional benefits over the functional ones. Shooting for the next pithy “Think Different” or “Just Do It” tagline is putting the cart before the horse, she says.

“As Matt Lerner pointed out in his language/market fit Review piece, Nike and Apple earned that right to be elusive over decades. But when you're an innovative little startup, you haven't yet. You need to be really clear and functional until people understand what you do,” Jackson says. “Challenge yourself to say, ‘What is the most bare-bones, functional way I could phrase this?’” She shares a few examples as inspo:

- “I worked with Loom and we landed on ‘Record instantly shareable videos of your screen and cam,’ which is exactly what they do.”

- “I worked with Rupa Health through First Round, whose benefit is, ‘Order, track and get results from 20 lab companies in one place.’”

- “Peloton’s early headline literally said, ‘Join studio cycling classes from the comfort of your home.’ That was the functional benefit they needed to reinforce before they could stay stuff like, ‘Together, we go far.’”

To stay laser-focused on the functional, Jackson suggests another simple exercise: “In the story of Cinderella, what is the super functional thing that happened? She had a fairy godmother who turned her pumpkin into a carriage. On the emotional side, she lived happily ever after. And right in the middle — she married a prince,” says Jackson.

Run through a similar brainstorm as you’re thinking about benefits. “List all the functional, straightforward benefits you have, all the emotional benefits you have, and all the ones in between. Try to stay focused more on the functional side of the ledger,” she says.

Especially if you're establishing a new category, you have to make sure people understand what the hell it is you're talking about before you can move higher up Maslow's hierarchy in your messaging.

If you’re eager to learn more from Jackson firsthand, we’d highly recommend her cohort-based course powered by Maven.

24. Sign up for the side gigs.

After joining as Stripe’s 28th employee, serving as Notion as Head of Platform & Partnerships, and advising founders as an early-stage investor, Cristina Cordova has assembled an impressive collection of lessons on building and scaling startups — something we were eager to tap into after she came aboard First Round last year. Here’s one gem that stood out:

“Elad Gil talks about ‘gap fillers,’ and I’ve always thought it’s the perfect phrase. Stripe was growing so fast that we needed people to plug holes in the organization,” she says. “That’s why you need to sign up for the side jobs. My core focus at Stripe was on partnerships, but I always had responsibilities on top of that. At one point, an engineering manager left, so I took over managing the team. I also led DEI initiatives for over a year before we made a full-time hire,” says Cordova.

“These opportunities allowed me to build a reputation and gave me more exposure to other functions for my own development. Promotions often require work that has cross-org impact, which these kinds of projects can help with,” she says.

But it’s not just about padding your own resume. “It’s very easy to fall into a mindset where you’re criticizing all the things that aren’t going well — it’s much harder to come up with a proposal for making things better. Are you constantly looking around to find new ways to help the people around you? Instead of being super frustrated by how busy your manager is these days, is there something you could do to help them get more leverage?”

It’s essential to grow with the company — rather than having the company grow around you.

25. Shield your company’s old guard by creating a culture of documentation.

“A lot of early-stage employees become the heroes of the company. They build a lot of features, solve major outages and come up with novel ways to improve the infrastructure. As the company grows, more folks come in and, without things written down, that old guard gets bombarded with questions,” says David Nunez, an early docs leader for Stripe and Uber. “Suddenly, all of the value these early heroes delivered initially, which was building and shipping, they now have much less time for.”

That’s where sharp internal documentation comes in. But you may be surprised that Nunez’s main piece of advice when it comes to internal docs isn’t to necessarily go out and hire someone to fix the problem for you. “I’ve learned that, especially in high-performance environments, changing the culture is the highest leverage investment you can make,” he says.

You’ll see meaningful progress quickly if you first address incentives and rewards for writing and maintaining documentation — or lack thereof.

Here are a few tactics for creating a culture of documentation:

- Make it a part of the job ladder: “I’ve found that if you codify knowledge-sharing expectations in job descriptions and job ladders, folks will inherently look to fulfill those responsibilities on their ladder.”

- Shine a spotlight, even outside of performance review season. “One manager included their ‘doc star of the week’ in each weekly update she sent. It’s such an easy thing to just call people out, and folks love to be recognized — especially for doing something outside of their comfort zone.”

- Carve out the time. He’s also seen other teams do “docs bashes” (like bug bashes) where the whole team will spend a day, or even a week, just working on documentation. “Make a leaderboard and see how motivated engineers get to contribute.”

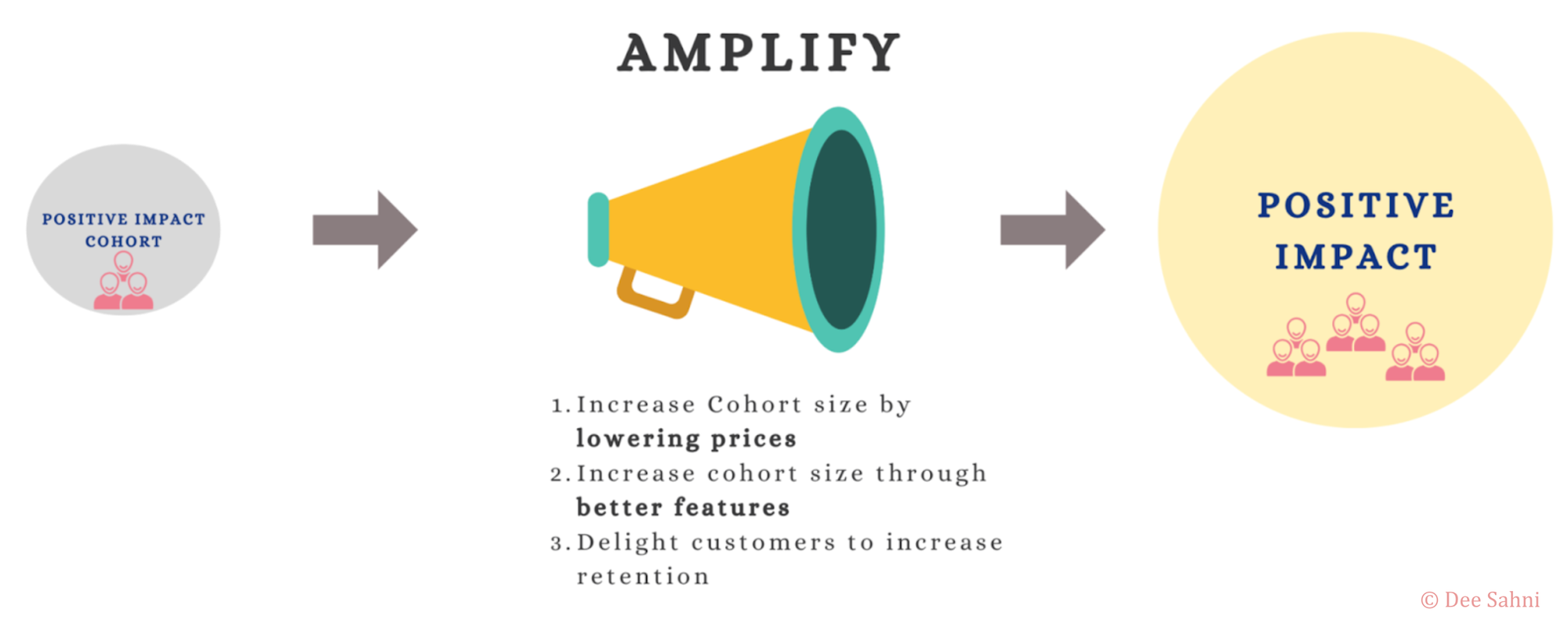

26. Amplify high-performing cohorts for better unit economics.

As a monetization leader and pricing advisor, Dee Sahni sees people try simple math to improve their unit economics: raise prices = more lifetime value. Instead, she coaches folks to approach pricing with a more bespoke technique for greater longevity, moving away from one-size-fits-all and towards granularity.

Powerful monetization doesn't take away from customer experience. It rides on it. In the best cases, it improves the experience. Thoughtful monetization can even reduce prices.

To demonstrate this, she sketches out some ideas for amplifying high-performing cohorts with custom pricing.

“When a cohort is over-performing, (like a high-retention, high-LTV cohort), you’ll want to amplify its impact by increasing the cohort size, or increasing retention — or both,” says Sahni. Common tactics include:

- Increase cohort size with lower prices, improving conversion rates: “Increasing the size of a high-retention cohort will drive average retention up. As an example, many companies increase the size of high retention cohorts by offering lower prices for longer subscriptions.”

- Increase cohort size through better feature sets and better conversion rates. “Amazon Prime grows the size of its high-retention cohort by offering the free deliveries feature.”

- Delight these customers to further improve retention and repeat purchases. “Loyalty programs, discounts and rewards are easy ways to show these customers they're valued. Nordstrom is famously known for its stellar customer service as a means to retain high-value customers. Similarly, Wayfair offers members-only discounts to reinforce loyalty.”

27. Skip buzzwords and lead with authenticity.

As the former Senior Director of Talent Acquisition, Shreya Iyer spent 11 years at Splunk, growing her career alongside the analytics automation platform. As one of the company’s early Talent hires, Iyer is particularly obsessed with employer branding. She’s experimented with dozens of tactics over the years as she’s watched Splunk’s own brand grow and change from scrappy upstart to publicly-traded BigCo.

Even if your startup doesn’t have a fully formed brand yet, it’s much easier to see the ingredients of your company culture with a headcount of ten versus a hundred. Iyer says this can be used as your differentiator when hiring candidates. And it doesn’t need to be serious.

“Before anyone knew what Splunk was, they’d probably seen the company on our swag. We had a penchant for funny t-shirts, with phrases like ‘Take the SH out of IT,’ or ‘I like Big Data and I cannot lie.’ Maybe folks rolled their eyes a bit, but they remembered us,” says Iyer.

It was embracing these quirky, humorous traits early on that ultimately made Splunk stand out. “One of our founders, Eric Swan, would make comments in interviews that Splunk was actually just a t-shirt company that happens to sell software. The company really embraced that humility as part of our character, and that low-ego culture shone through in our interviews with candidates,” she says.

28. Bucket your design partners to maximize their impact.

In the early days of product-building, the transition from internal dogfooding to putting your product out in the real world can be a sizable leap — that’s where design partners can help cushion the fall. But when trying to sign up design partners for enterprise infrastructure product Cockroach Labs, Chief Product Officer Nate Stewart didn’t exactly have folks lining up the door to be early testers.

His advice to other product leaders facing similar headwinds is to bucket your design partners into different categories:

- Strategic Design Partners: “With these folks, we talked about where we thought the database market was going. What were some of the macro problems that people were experiencing and the pains that their organization was going through?”

- Roadmap Design Partners: “These were people providing feedback on the actual roadmap and the capabilities that we want to add to the database. For example, it was clear over time that if people are installing a mission-critical database, they want it to plug into the rest of the organization and send updates to other systems in real-time. So we talked about adding a real-time data streaming capability to the roadmap — there was a lot of excitement around that and the design partners helped us de-risk the engineering investment it would take to build.”

- Feature design partners: “This is the most difficult design partnership, which is getting engineers to try particular features. These are the design partners who feel the most pain that your product can solve. For example, we had an early customer doing a significant amount of payment processing, and all of that was happening in a single data center. If that data center went down for any reason, their business would be completely offline. They had to build a more resilient system, and they were willing to invest a couple of engineers to make sure that Cockroach would help them evolve to a cloud-native architecture.”

MBA-style reports about market size are great. But when you start to see the conviction from your design partners, you get a picture not just academically of how big a market is — you start to feel it viscerally.

29. Use inflection points as markers to evaluate company culture.

Part of what makes a startup’s gravitational pull so strong for its employees is the values. Before even landing on a tangible product idea, founder Laura Del Beccaro was obsessed with company culture — squirreling away bookmarked reads, inspiration and ideas for the culture she dreamed of building.

But crafting a shared system of beliefs isn’t a one-and-done exercise for companies just starting out. “Whenever there's an inflection point at your company — a fundraise, a big market shift, a strategy shift, a change in leadership, a layoff — these are all good times to re-evaluate,” says Del Beccaro. “ What things do you want to hold onto or change as you scale?”

To kick off this cultural pulse check, Del Beccaro offers a brainstorm (as part of a five-step framework) for how companies of any size can re-group and re-evaluate the culture:

- For co-founders just starting out: Ask yourselves questions like, “It’s five years down the line, and everyone is actually living out the values we selected. What would a company that we’d be proud of look like?” or “If you took 6 months off, and left no directions other than ‘Follow our values to a T,’ would you be happy with the outcome?”

- Early-stage companies: “If you’re still on the small side, have everyone at the company think about the qualities in leaders or direct reports that they’ve valued in the past. Then get each person to answer two questions: ‘What do you believe are the currently held values of the company today?’ and ‘What values would you like to see our company adopt?’”

- Later-stage companies: If you’ve got hundreds of employees already, try this variation: “Create a manageable number of ‘cultural ambassador’ groups, pulling individuals who opt-in across teams, levels, and backgrounds to run their own separate brainstorms and present their findings in a templated format. Then use a tool like Dovetail to find trends,” says Del Beccaro.

30. Try a multi-pronged approach for tracking your work.

After joining Levels in her first-ever Chief of Staff Role supporting co-founder Dr. Casey Means, Sonja Manning found that she quickly ended up with a to-do list miles long. To tackle the mix of short and long-term priorities, she developed a five-part system that other folks may want to borrow for keeping all the balls in the air:

- Daily to-do lists organized into categories: read, write, think. “This helps me set an achievable plan for the day and the week. At the end of every day, I go back through and jot down how long each thing actually took me to complete, which provides the opportunity for an instant brief reflection.”

- A weekly and monthly priorities doc where we track the executive’s weekly 3-5 priorities and five monthly priorities. “This, along with our calendars, becomes a retrospective for what was accomplished in a week.”

- An ongoing discussion doc with a running list of items. “Items get checked off after they’re discussed or completed. This reduces cognitive burden because everything has a place and lives there until it is done.

- Calendar showing when the work will happen. “As an aspirational, ‘Rome could be built in a day’ type of person, tracking exactly when I will accomplish tasks on calendar blocks is essential in keeping me honest about what I can achieve in a workday. Often, if I’ve blocked a task for 60 minutes and after 60 minutes it’s not done, I’ll either ship the version I have or re-scope the task.”

Tracking tasks on your calendar is a great forcing function for shipping work that’s less-than-perfect (because, when it comes to startups, perfect is the enemy of good).

Top illustration by Alejandro Garcia Ibanez, featuring (from left) Sam Corcos, Phaedra Ellis-Lamkins, Annie Duke, David Nunez, Ximena Vengoechea.