The product strategy is an important product management artefact. But despite its significance, it is not always effectively used. In this article, I discuss ten common strategy mistakes I see people make so you can avoid them and successfully leverage the product strategy.

Listen to the audio version of this article:

1 No Strategy

The first and most crucial mistake is to have no product strategy at all. When that’s the case, a product is usually progressed based on the features requested by the users and stakeholders. As there is no strategy, objectively assessing the impact of the requests is virtually impossible. Consequently, whoever shouts the loudest or has the biggest clout gets their features implemented. This can result in a Frankenstein product, a product that has a horrible value proposition and offers an awful user experience instead of creating real value for the users and the business.

2 Wrong Level

Another mistake I see people make is to focus their product strategy on the portfolio or feature level rather than the product. The strategy is therefore either too big or too narrow.

While it can be beneficial to use a strategy that maximises the value a product portfolio creates, I generally recommend keeping it distinct from the individual product strategies and using separate artefacts to capture the plans. Take a productivity tools suite like Microsoft Office or Google Workspace. If I was in charge of such a portfolio, I would use an overall strategy for the entire suite and separate product strategies for the individual tools like Microsoft PowerPoint and Google Slides.

Using, however, a strategy that focuses on one or more features is not something I would advise. Take PowerPoint and Slides to stay with the previous examples. Having a strategy that covers, say, the ability to persist and retrieve slides is usually neither necessary nor helpful. Instead, it creates additional overhead, as the feature strategies have to be updated and aligned.

If you find yourself struggling to come up with an effective strategy for an entire product, then this may be an indication that the product has grown too big and has become too heterogeneous. Instead of introducing feature-based strategies, consider unbundling one or more capabilities and creating product variants. This will result in more focused products with clearer value propositions, as I discuss in more detail in my book Strategize.

3 Incomplete

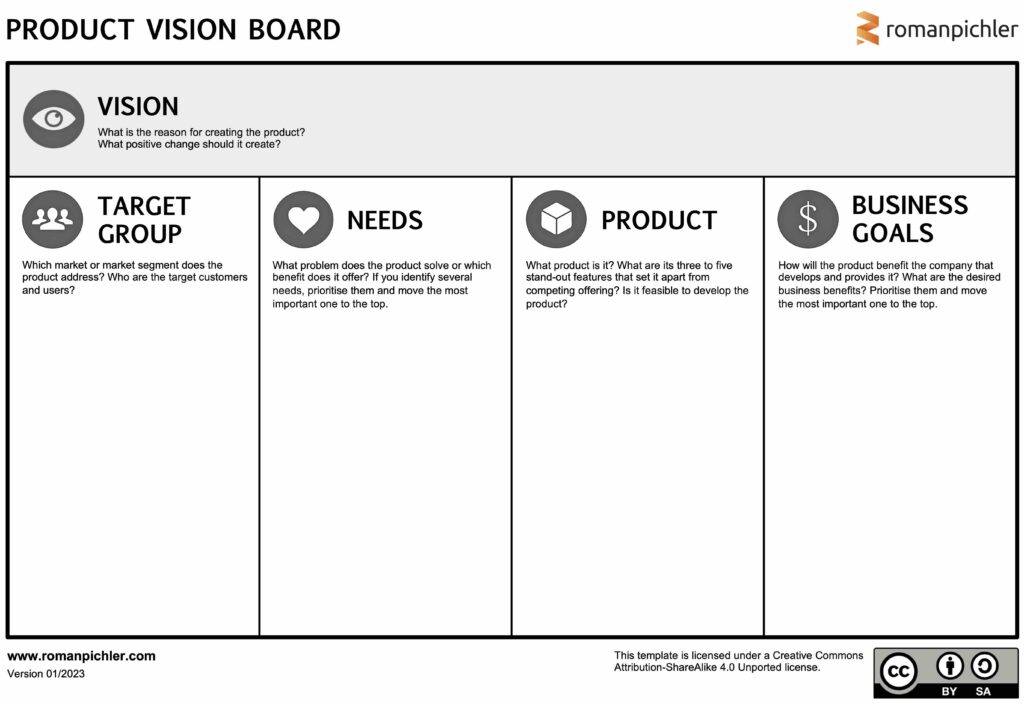

An effective product strategy describes the approach chosen to achieve product success—to offer a product that solves a problem or creates a tangible benefit for the users and that generates value for the business. But not all strategies I have seen contained the right information. To avoid this mistake and ensure that your product strategy is complete, answer the following four questions:

- Who are the (target) users and customers of the product?

- What is its value proposition? Why will people want to use it or pay for it?

- What are the benefits the product should generate for the company developing and providing it?

- What are its standout features—the capabilities that set it apart from alternatives and entice people to choose it over competitor offerings?

A handy tool to capture your answers and describe the product strategy is my Product Vision Board shown in the picture below. You can download the template by clicking on the image and you can find more advice on how to use it in the article The Product Vision Board.

4 Unspecific

It’s not uncommon for me to see product strategies that are too vague and coarse-grained. For example, the target group might be too big and diverse; there might be too many needs stated and they are too unspecific; the business goals might be unclear; or the standout features might be weak. Such a strategy does not provide sufficient guidance and direction. It consequently fails to align the stakeholders and development teams.

While it’s perfectly fine to start with an initial, sketchy strategy, you should spend the necessary time to sufficiently refine and detail it. If you struggle with this, then you might either lack the necessary knowledge or how might shy away from making tough decisions. In the first case, carry out just enough research work so you can clearly state the target users and customers, the specific problem the product should solve, the business impact it should achieve, and the three to five features that will give it an advantage over competitor offerings. In the second case, bring to mind that making strategic decisions requires focus. It involves discarding ideas and declining requests. As Steve Jobs once said, “Innovation is saying no to 1000 things.”

5 Not Evidence-based

It’s a mistake to base a product strategy on intuition and past experience, the views of influential stakeholders, or the ideas of the CEO. Instead, it should be grounded in empirical evidence in order to avoid arguments and maximise the chances that the strategy will result in a successful product.

A great way to achieve this is to create an initial strategy and then systematically validate and refine it following an iterative, risk-driven approach. Start the process by selecting the biggest risk: the uncertainty that must be addressed now so that you don’t make the wrong strategic decisions and you don’t take your product down the wrong path. This might be the risk of addressing the wrong target group or need. Next, determine how you can best address this risk, for instance, by observing target users, interviewing customers, or building a prototype. Carry out the necessary work and collect the relevant data.

Then analyse the results and use the newly gained insights to decide what to do. Ask yourself if you should stick with your strategy (persevere), significantly change it (pivot), or stop the innovation initiative (kill). If you decide to pivot, rework the strategy, and restart the validation process; if you persevere, update the plan, and select the next key risk.

Follow this process until your strategy no longer contains any significant risks and you have sufficient data to show that it is likely to result in a desirable, feasible, viable, and ethical product. The picture below summarises this approach, and you can find more guidance on strategy validation in my book Strategize. Note that the process shown is loosely based on Eric Ries’ work.

6 Disconnected

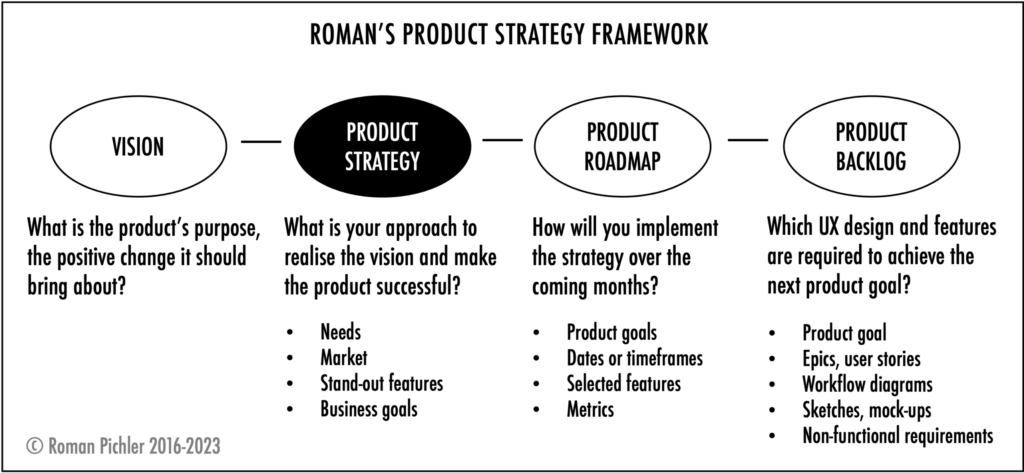

As I mentioned before, the ultimate purpose of a product strategy is to offer a successful product—a product that creates value for the users and the business by offering the right user experience and the right features. To achieve this, the strategy must direct product discovery and delivery; it must be connected to the product backlog and help determine which functionality is implemented.

It’s therefore a mistake to treat the product strategy in isolation and not connect it to other plans, especially the product roadmap and product backlog. In the worst case, a chasm between strategy and delivery exists: Strategic decisions are not translated into tactical ones, and insights from product delivery aren’t used to evolve the product strategy.

To avoid this issue, adopt a holistic approach and systematically link your strategy, roadmap, and backlog. You can achieve this by following my product strategy model, which is shown in the image below.

In the framework above, the product strategy directs the roadmap, and the roadmap guides the backlog. At the same time, bigger product backlog changes can trigger roadmap updates, which, in turn, can lead to strategy adaptations, as I explain in more detail in the article My Product Strategy Model.

7 Fixed

Another error is to view the product strategy as a fixed plan that simply has to be delivered—rather than a fluid one that will change. As your product develops and grows, and as the market and technologies evolve, you must adapt the product strategy. Otherwise, it won’t be any longer a valid, forward-looking plan that offers effective guidance.

You should therefore take the necessary time to regularly inspect and adapt the strategy—at least once every three months, as a rule of thumb. Asking the four questions below will help you with this, as I discuss in greater detail in the article Tips for Effective Product Strategy Reviews.

- Performance: What do the key performance indicators (KPIs) tell you about the value your product is creating? Are you on track to meet the needs and business goals stated in the product strategy?

- Trends: Are there any new technology, regulatory, or social developments that you should respond to by adapting the strategy?

- Competition: Is your product still sufficiently differentiated? Does it offer a clear reason for people to choose it over alternatives?

- Company: Are there any significant business changes that affect the product strategy? For example, has the business strategy changed?

8 Lack of Buy-in

The most amazing product strategy is useless if people don’t buy into it and follow it. It’s therefore a mistake not to secure the support of the key stakeholders and development team members. To avoid this issue, generate the necessary buy-in by involving the individuals in the strategizing work. A great way to achieve this is using collaborative workshops and choosing a decision rule such as unanimous agreement or consent. This does not only increase the chances that people will support the strategy. It also allows you to leverage their expertise to make the right decisions.

While you should aim to generate as much support as possible, be careful not to appease people or allow individuals to dominate the decision-making process. Instead, search for a strategy that maximises the value the product creates and at the same time, attracts as much support as possible.

Deciding together does not mean that everybody gets their way or is necessarily super happy with every decision. It means finding a product strategy that achieves product success and attracts as much support as possible, as I explain in more detail in the article Making Effective Product Decisions.

9 Lack of Effective Ownership

It’s not uncommon in my experience that the head of product—also known as Director of Product Management, VP of Product, or Chief Product Officer—owns the product strategy and has the final say on strategic product decisions. While this can be an effective temporary fix, I regard it as a mistake when it becomes a permanent solution.

Instead of the head of product, the people developing and providing the product—the product team—should collaboratively create, validate, and update the strategy, and the person in charge of the product—the product manager or Scrum product owner—should be empowered to have the final say if no agreement can be reached.

But with great power comes great responsibility: The individual managing the product has to ensure that there is an effective product strategy that guides people’s work and that is likely to result in a successful product.

10 Strategy Cult

The final mistake I see people make is to believe that there is one right way to create and evolve a product strategy. I freely admit that I’m biased, as I’ve developed my own strategy approach. But the point is not to blindly follow a process or implement a tool but to determine if and why a product should be offered, and how it can create tangible value for the users and the business.

If my product strategy model and the Product Vision Board resonate with you, then that’s great. But if you prefer to use, for example, Impact Mapping or Gibson Biddle’s DHM model, then that’s also great. I think it’s wonderful to have different options and be able to select the approach that works best for your product and organisation.

Post a Comment or Ask a Question

2 Comments

I love that and it’s so true. Thank you for this.

You’re welcome Charmaine and thanks for the feedback. It’s great to hear that you liked the article.